Please reference this article as Theatron Vol. 15, No. 4. (2021): 5–19. (See the PDF file at the end of the Table of Contents.)

After the end of World War I and the collapse of four empires (Austro-Hungarian, German, Ottoman and Russian), several new European states were created. They offered a different identity and image of the Old Continent in response to war. There were rapid changes, new ideas, the world was full of hope and positive energy. Although artists came from different cultural and historical backgrounds, they shared the same disillusions because of the war disasters and had similar antiwar aspirations. Positive perspectives about Europe and the world, and about a peaceful cosmopolitan future prevailed – at least for a while. The central part – the so-called “heart of Europe,” was not well known; it was considered peripheral, and in many ways it remains so until today, even though Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria are all members of the European Union. Without arguing about how realistic, autochtonous or homogeneous Central Europe really is (the territory is primarily the successor of the former Habsburg Empire) – we will begin with the assumption that there really is such a thing as “Central Europe.” It is important to emphasize that two remarkable art historians, professors Andrzej Turowski1 and particularly Krisztina Passuth2 were among the first experts who contributed to raising the awareness about the richness of ideas, variety of manifestations, important art works and outstanding figures in the avant-garde sphere of the Central European cultural milieu. On the other hand, we must also accept Timothy O. Benson’s3 considerations of the complexity of Central European identity as “ambiguous, diffuse, fragmentary, and contradictory”: “Not one avant-garde, but many avant-gardes, interacting with one another yet each retaining its unique characteristics”.

Young generations of writers, poets, artists, theorists, philosophers, architects, musicians, and film makers helped editors in the early 1920s revitalize the cultural life of the region by, among else, publishing a variety of reviews, journals or magazines supporting new ideas and radical forms of expression, often connected to progressive social positions and leftist influences. In spite of different orientations and local historical or social conditions, different languages used, frequent changes of locations and even countries where those reviews were edited, they often had similar objectives. They had clearly expressed attitudes about multinational and cosmopolitan culture, and they supported new forms and fresh ideas, with an ideological commitment to considering culture as primerely a social issue. The editors exchanged articles, manifestos, poems, reproductions of plastic and applied arts, thoughts and practices in theatre, film, music, photography and architecture. They invented new media, organized international exhibitions, performances, soirées, conferences; participated in provocative activities and discussions with radical slogans about the need to improve the conditions of institutions and, in general, to change social and often also the larger political situation. They stimulated dialogues between the traditional and the modern and were among the first to understand the importance of new technical and technological developments which they introduced to their publications and activities. In this rush to present and even accept new events and new statements, we can sometimes recognize the overlapping of different – if not opposed – phenomena, with a dynamic structure, diverse subjects and a variety of stylistique forms.

In spite of this very active, frequent and fruitful international communication, cooperation and sharing common ideas about utopian expectations, the avant-garde reviews could not contribute to the creation of a united and unique avant-garde movement. Therefore we will discuss different avant-garde “voices” in Central European reviews and their particularities within distinct cultural, historical, political and social conditions; their isolated expressions but also often with very close points of view.

Reviews were important as the easiest and most direct, independent way to express and confront statements and ideologies, to gather people with same or similar attitudes, to be international and interdisciplinary, able to enlarge the number of collaborators from distant locations, to be, in a word – a forum for the exchange and dissemination of new ideas and complex new tendencies in various disciplines. It is incredible how this communication was intense and quick, rich and productive – in spite of the only possible technology of that time – traditional letters delivered by mail, and sometimes direct contacts among the involved editors and artists established in big cultural centers – Paris, Vienna, Berlin.

Both the similarities and the differences evident in these reviews will reveal simultaneous autochthonous and independent developments in their respective milieus. At the same time, however, the major European metropolis and the unofficial European capital of that time, Berlin, was extremely important as the meeting point and the crossroads of artists coming from the East and from the West. Above all, there was Herwarth Walden and his Der Sturm, established in the 1910s, as an example and a source of information. However, it also offered space for presentations of fresh ideas and forms coming from all over the world, including various Central European artists. There were many Hungarians in Berlin who left their country because of Miklós Horthy, or Bulgarians who escaped from Cankov’s dictatorship, Romanians and Austrians, Poles, some Croats, Slovenians and Serbs, Ukrainians and Belarusians, but mostly – hundreds of thousands of Russians of all colors, white and red, left and right, progressive and conservative, gathered round the Nolendorfplatz. The so-called Russian Berlin had a particular role in spreading outside of Russia the ideas of utopian Constructivism, headed by Lazar El Lissitzky, as well as the short lasting review Veshch/Objet/Gegenstand, which he edited together with Ilya Ehrenburg. Ehrenburg’s momentous novelIt does Revolve was reflected in some Central European avant-garde reviews, as it was the First Russian Exhibition of New Art in the Van Diemen Gallery from October to December 1922.

Reviews and the emerging ideas were often presented and developed in popular cafes that the artists occupied at that time, such as Japan Café or Café Central in Budapest, Narodni Café, Slavia, Tumovka, Union or Metro in Prague, Polish art Club in Polonia Hotel in Warsaw, Kasina and Korzo in Zagreb, Moscow in Belgrade, Café Capsa, Teresa Otelesteanu or Café Enache Dinu, near Bucharest Piata Mare, Schloss Café and Café Beethoven in Vienna.

Among the very first, most influential and longest lasting avant-garde journals, reviews or periodicals, probably in the entire Europe, was the antiwar review MA [Today], representative par excellence for our narrative. FIG. 1 It appeared in 1916, succeeding the review A Tett [The Deed], banned during World War I. The founder, the charismatic Lajos Kassák and his Activists celebrated social justice and the moral role of art, revolutionary changes not only on the political but also the technological level. They strongly emphasized and promoted new values of industrial production, design, architecture, technology and all other new inventions, such as photography, collages, photomontages, new typography and newly invented alphabet. After supporting the ideas of Cubism and Futurism, MA embraced Dadaist humor and sarcastic behavior. Kurt Schwitters’ picture-poems were reflected in Kassák’s works. His picture–architecture became a proto-model for geometrical compositions: proto-Constructivism appeared here for the first time. Exceeding Russian Obmokhu, the review became the loudspeaker of the most radical pan European Constructivist abstraction, “social and technological utopia”, or “Romantic Constructivism”, according to Ilya Ehrenburg. Artworks that appeared in Ma were identified as promoters of a better world to come. Kassák believed that it was a symbol of a future without nationalism and social class stratification. The review had a great impact on other avant-garde periodicals almost all over Central Europe: after Kassák’s articles and woodcuts appeared on cover pages of MA, they were soon replicated in Der Sturm and Veshch/Objet/Gegenstand in Berlin, Zenit in Zagreb/Belgrade, Contimporanul in Bucharest, Zvortnica in Cracow, etc.

The year 1922 was important for the Hungarian avant-garde: after the collapse of the Commune, Kassák and Activists chose Vienna as their new stage. An even larger international collaboration was established with deeper Communist influence, particularly in Béla Uitz’s journal Egység [Unity]. Quoting Jaroslav Andel, Oliver A. I. Botar argues:

“The Hungarians’ concept of »Proletcult« was equivalent to what was known in Soviet Russia as »Proletarian Art«, e.g., art in the service of the Communist Party. »Proletarian Art« was not only separate from the Proletcult, an autonomous movement founded by Aleksandr Bogdanov and others to encourage artistic production among workers, but was promoted by the Party in opposition to it.”4

Dadaism became visible in Sandor Barta’s Akasztott Ember [The Hanged Man] – together with Proletcult ideas and simplicity of its expression, on the one side, and on the other, with George Grosz and Berlin Dada there was humor full of satire, sarcasm and absurdity. In that respect it was similar to the spirit of Yugoslav Zenit or Romanian Urmuz. Although Kassák rejected Dadaist mood in his MA, he considered the Hungarian Dadaists’ review Ūt [Path] from Novi Sad & Subotica (in Voïvodina) as a “brother’s review”. Kassák and Moholy-Nagy published their important overview of different avant-garde movements in the book Buch Neuer Kunstler (Book of New Artists). Moholy-Nagy’s Picture-architecture (Bildarchitectur) manifesto was accepted as a guide to spiritual constructivism.

Ma had a rather dissolute organization, with various interests and backgrounds during its long life. Important participation of various Hungarian artists such as Béla Uitz, János Máttis Teutsch, Iván Hevesy, Sándor Bortnyik, Lajos Tihanyi, Aurél Bernáth, Lajos Kudlák, and “prophetic poets” Endre Ady, János Mácza and Béla Bartók created a rich scenery for the review’s concept. Ernő Kállai was the key link to the international context. On the other hand, Socialist Berlin was present through connections with Franz Pfemfert’s journal Die Aktion. Collaboration with other progressive magazines, institutions and figures was intense as well, such as for example, with Periszkop and Genius in Arad (Transylvania), with Hannes Meyer, Bauhaus etc.

Back in Budapest in 1926, new challenges did not surprise Kassák: in his review he gave support to another international uprising movement, Surrealism, confirming his permanent confidence in art as a social activity but without political involvement.

In cosmopolitan Prague, the cultural atmosphere was favourable for new events: there were plenty of exhibitions, collections (for example the famous Vincenc Kramař’s early Cubist collection with works of Picasso, Braque and other French painters), in addition to emerging local new art movements such as Czech Symbolism, Cubo-Expressionism based on local Baroque experiences with Otto Gutfreund, Bohumil Kubišta or Antonin Prochàzka, followed by specific Czech Cubism in art, design and architecture. The entire Prague cultural scene, where Franz Kafka lived, Roman Jacobsen worked as a distinguished linguist, Albert Einstein lectured, many prominent European artists visited and White Russians stayed after the October revolution, contributed to the intellectual environment and creativity of the 1920s.

Umělecký Svaz Devětsil [Art Union Nine Powers], the art group and avant-garde movement, founded in 1920 in Prague and in 1923 in Brno, had a loose program in the early period, combining different ideas and aesthetic platforms, first of all willing to mobilize the post-war energy and creative potentials of young artists. The first phase was close to Expressionism, combined with Magic Realism and Primitivism or Primordialism. This early Czech modernism was immediately represented in the review Zenit, Zagreb, nos. 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10, 1921. FIG. 2 The leading theoretical figure Karel Teige, who in a way had a similar role as Lajos Kassák in Hungary, was at the same time an eminent writer, poet and radical plastic artist. He advocated clear proletarian positions, especially after his visit to the Soviet Union in 1925. For him, art should be connected to social life and in that respect all the limitations should be abolished through new forms of creativity. Therefore, he supported new experiments in art, such as the technique of photo-collages where film procedures of cutting and interpolation were practiced, or new typography, as well as real objects from everyday life introduced into the exhibitions, both in photos or as “ready-mades”. Teige created his picture – poems as the basis of Czech Poetismus, which was “not one more ism, but the necessary complement of Constructivism” – according to his statements. Poetismus was gradually moving towards Surrealism, both in literature and in plastic and visual arts, and Devětsil was its full supporter.

Devětsil members published a series of publications: the regular monthly review ReD [Review of Devětsil], Disk, Pasmo [Zone], Stavba [Construction], and also important almanacs in 1922 – Revolučni sbornik Devětsil [Revolutionary Collective volume Devětsil] and Život [Life] I & II with a great number of international contributions (among others – Yvan Goll, Ilya Ehrenburg, Jeanneret & Ozenfant, Micić etc.). Beside the charismatic Teige, very active were painters Jindřrch Štyrskŷ and Toyen (Marie Čerminova). Already living in Paris for years, they were close to leading Dadaist and Surrealist circles around Breton, Arp, Dali, Max Ernst, Masson, Miró, Paalen, Tanguy, Giacometti, De Chirico etc. Therefore it was not surprising that Surrealism would be present early in major Czech avant-garde reviews.

Great contribution was given by Czech poets and writers, such as Jaroslav Seifert, Vladislav Vančura, Adolf Hoffmeister, Jaroslav Rössler, Bedřich Václavek, Konstantin Biebl, Vítězslav Nezval or Jiří Voskovec, leader of Osvoboždene [Liberated] Theater, who put on stage progressive plays by Alfred Jarry, Apollinaire, Breton and Cocteau.

Important activity was realized by the Architects’ club with participation of many local members and also with contributions by Pieter Oud, Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, Adolf Loos, Theo van Doesburg and many other prominent architects. Czech Functionalism immediately attained special recognition worldwide.

Among the most attractive Devětsil activities were exhibitions and anti-exhibitions, which were reflections of the Berlin Dada Fair. After the first, Jarni vystava [Spring exhibition] in 1922, the following exhibition, Rudolphinum first in Prague and then in Brno in 1923–24, was much more radical: called the Bazaar of Modern Art, this exhibition expanded the notion of exhibits. It included stage design and architectural projects, reproductions exposed close to the original works, special combinations of pictures & poems, photomontages, fashion design, installations, such as mirrors instead of portraits, or window dummies instead of sculptures…

The next show organized by the Review was held in 1926 when Constructivism and Poetismus dominated. The exhibits promoted machine production, modern technology and the technical world. The “electric century” glorified telephone, radio, airplanes, railroads, ships and cars. The new order was established – emotions were governed by mathematical laws, not by individual expressions in art. In a way, this preceded the ideas of L’Esprit Nouveau. Teige declared that no more pictures in frames are needed, originals will disappear, and instead reproductions and prints will dominate.

Devětsil was quickly acknowledged abroad and became also an important part of the local scene, which was not the case with many other reviews of that period in other cultural milieus.

Another distinct periodical Fronta appeared in 1927 in Brno under the slogan “an international journal for current activity”. Its editors František Halas, Zdenek Rőssman and Bedřich Vaclavek summarized the actual state of art and culture, with another socialist idea. According to them: “The new art in life is to create new people who will create a new society”. Little by little – all those utopias will sink in deep seas of different aspirations and ambitions, and not only in Czechoslovakia…

Since Poland also obtained its independence and unification in 1918, a new strategy for rediscovery of national identity was developed, with new ideological expressions, but without Dadaist sarcasm or irony, like in many other countries. They had some typical local issues. It was believed that folk elements may offer truly national, unique, archetypal and eternally modern and original spirit. In that respect a group of Formists put its roots of modernism in Poland. Supported by the great Polish and European writer Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz – Witkacy, Formists represented a variant of Polish Cubism, with some Futurist and folk elements. They stated that the aim of painting is not to reproduce the real world, but to construct an unbreakable whole from various planes. This was the path towards Constructivism.

In May 1923 visual artists organized an exhibition with a very special installation in a special place – the luxury car show room, in a way similar to the Czech Bazaar: postcards replaced traditional painted landscapes, periodicals and books on modern art were displayed together with works of art. This exhibition stimulated the foundation of an art group called Blok – Group of Cubists, Constructivists, and Suprematists (1924–26). They were editing the homonym review Blok in Warsaw, also active in Vilnius. FIG. 3 Here again the general concept had a strong social commitment, reflected in theoretical writings and pragmatic art works. The most prominent representatives were Henrik Berlewi, Mieczysłav Szczuka, Teresa Žarnower (Žarnowerówna), WładysławStrzemiński and Katarzyna Kobro. In the Blok Manifesto “What is Constructivism?” we recognize the closeness to the concept of Alexander Rodčenko’s Lef (Left Front of the Arts), especially when questions about the relationship between art and social revolution are raised. The same goes for utilitarianism and industrial production in service of social change. Mechanical objects were reproduced, and use of new materials stimulated (iron, glass, cement). Consequently – new forms were expected. Szczuka and Žarnower, on the other hand, attended Vhutemas (Vysshiye Khudozhestvenno-Tekhnicheskiye Masterskiye [Higher Art and Technical Studios]) and accepted positions of El Lissitzky and Naum Gabo.

Władysław Strzemiński, artist, critic, theorist, teacher and organizer of cultural life in Lodz,the author of the most radical concept in Polish avant-garde Unism, had a distinguished international career: as a Belarusian, he was one the most prominent Polish avant-gardists, who also contributed to the organization of the first avant-garde art exhibition in Vilnius (in Poland, at that time), together with his wife Katarzyna Kobro, a prominent Polish sculptor of Russian, Latvian and German origin. Their theory of Unism was influenced first by Moscow INHUK (Institut Hudožestvenoi kulturi / Institute of Art Culture), but soon their theoretical approach has changed: they announced the idea of a complete unity of various elements in the art work. Strzemiński’ s paintings found the inspiration in Unistic musical compositions by the Polish composer Zygmunt Krauze and he also created his architectonics – compositions in space – and was interested in making new typography. His revolutionary book The Theory of Vision speaks in a different way about Constructivism and its social purpose. Strzemiński stood for the idea that art should be autonomous and artists should have “laboratory conditions” in artistic experimentation. In that respect, for him, Productivism had a pejorative meaning.

The successors of Blok – the group Praesens (1926–29) and later a.r. (1929–36) were transferred to Łodz where the first Museum of Modern (e.g. Avant-garde) Art was created in one textile factory thanks to the artists Szczuka, Strzemiński, Kobro, Henryk Stażewski, and poets Julian Przyboś and Jan Brzękowski. It remains until now one of the most important museums for avant-garde art.

Łodz was also home of the influential Jung Idysz group and its publications that were introducing various Expressionist feelings, referring to Mark Chagall: Jankiel Adler, Marek Szwarc, Henryk Barciski, Ida Brauner, Neuman were its promoters. El Lissitzky, on his way from Vitebsk to Berlin, spoke in their club about international Constructivism. He also went to Warsaw.

The Cracow based review Zwrotnica [Railway Switch] was ideologically also on the left, launching new forms and media, thanks to the editor and poet Tadeusz Peiper who was an active and successful mediator: he introduced Polish avant-garde artists to the international scene, and among others also introduced Malevič to Gropius and Moholy-Nagy. In his review, he also supported Kazimierz Podsadecki, prominent constructivist and abstract painter, who made photo-montages and experimental films.

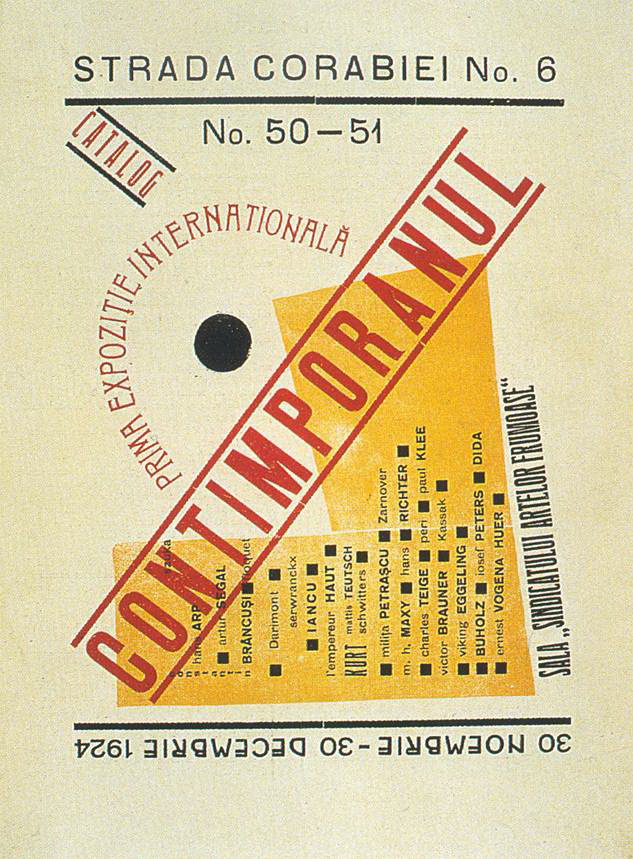

Contimporanul [The Contemporary] was an avant-garde political, satirical and art weekly journal, with plenty of fresh news and up-to-date comments, published in Bucharest since 1922. FIG. 4 It claimed to continue the tradition of the homonym former newspaper from Iasi, which was sponsored by Socialist societies in the 1880s. There was a new series from 1946 on, with a slightly changed name (Contemporanul) which continues to be published until today, but obviously without avant-garde connotations.

This political orientation of the review already changed in 1923, but the review remained committed to serious social issues, attacking anti-Semitism or bourgeois mentality. It was oriented more and more towards cultural and artistic subjects, treating Cubism, Futurism, Constructivism, and Surrealism (one entire issue was dedicated to it) and thus became the meeting place of journalists, editors, writers, artists and architects. The two major personalities responsible for Contimporanul avant-garde beginnings were Marcel Janco and Ion Vinea. Janco was once a prominent Dadaist, one of the organizers of the Zurich Cabaret Voltaire, although the Romanian review did not support Dadaism nor Tristan Tzara’s changed views regarding this movement. Ion Vinea was a fervent opponent of the ruling National Liberal Party and he was openly against art imitating nature; therefore he was struggling to find new forms and consequently a new reality. The review established international collaboration with numerous reviews all over Europe.

Radical, abstract Constructivism was not often present on the pages of this review because more attention was given to the synthesis called “integralism” of Cubism, Futurism and some forms of mild Constructivism. Little by little, the direction towards Romanian Surrealism prevailed due to the imaginative works with subconscious messages by leading Romanian painters Viktor Brauner, Jacques Herold and Jules Perahim (aka Iulius Blumenfeld).

Contimporanul paid particular attention to modern architecture, probably thanks to Marcel Janco’s revolutionary vision of urban planning nourished with some expressionist ideas of Cubist dynamism in construction. As a real Renaissance man, Janco made projects for various innovative constructions in the city center, and was recognized for his sculptures and reliefs with slight reminiscence to Constructivism, for his paintings, prints, illustrations, furniture and stage design; he also wrote essays on art, film and theater, arguing that “Constructivism is the left extreme of Cubism”.

The third important collaborator and editor of Contimporanul was the painter Maxim Max Herman Maxy, responsible for the organization of the International Exhibition of this review in December 1924 in Sala Sindicatului Artelor Frumoase (Exhibition Hall of the Plastic Artists Trade Union). He was assisted by Marcel Janco in organizing this huge show. The most impressive was the section of Romanian artists who sent their works from various parts of Europe: from Paris, Berlin, Rome, Zurich; among others, there were exhibits by Arthur Segal, one of the founders of Novembergruppe, Tristan Tzara’s portraits, Maxy’s and Janco’s constructions, Viktor Brauner’s Surrealist and Janos Mattis-Teutsch’s abstract paintings, four important sculptures by Konstantin Brancusi (Melle Pogany, Kiss, Maiastra and Child’s Head and a photo from his Paris studio), as well as several works of his student Milita Petrascu.

Beside works of modern art, the show had an eclectic agenda – it included Dida Solom’s puppets, East Asian idols, Ceylonese masks, applied art objects, architectural drawings, abstract designs, and Viking Eggeling’s films, alongside the works by Arp, Klee, Richter, Lajos Kassák, Kurt Schwitters and others (such as, for example, the Zenitist Jo Klek). The double issue (nos. 50–51) of the review Contimporanul served as a catalogue of the exhibition, as was the case of the Zenit exhibition in April 1924.

The inauguration of the Contimporanul show was in a Dada mood: with “Negro jazz” musicians as “modernist ritual”, drumrolls, sirens, inaugural speeches in darkness with candles. “It was chaos”, visitors remembered. There were no commercial issues, but many articles about this event remained.

Even earlier, while they were still in high school, Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco and Ion Vinea edited the magazine Simbolul [The Symbol] Also in early 1920s, a group of young revolutionaries in Yambol, Bulgaria, who opposed the mainstream cultural and social environment published a small review entitled Crescendo (1922), which published articles and reproductions by progressive Bulgarian artists and also included works by Celine Arnault, Ozenfant and Jeanneret, Teo van Doesburg, Tristan Tzara, Ilya Ehrenburg, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Benjamin Péret, Kurt Schwitters, Alexandre Tairov, etc. FIG. 5 This activity was possible thanks to the European contacts of the major figure in Bulgarian modernism, Geo Milev, a poet, writer, journalist, translator, and editor of several reviews (Vezni/Scales, Plamk/Flame etc.). He fell victim to Cankov’s dictatorship because of his famous poem Septemvri (September, 1924), which railed against the military coup d’état in June 1923.

There were several other Romanian avant-garde magazines with different concepts and positions: Unu (editor Sasa Pana) was a leftist periodical, making a transition from Romanian avant-garde to Surrealism; Urmuz (editor Demetrescu-Buzau) was the predecessor of absurdity in literature and new language; Integral (edited by Ilarie Voronca) preferred Futurist ideas; 75 HP was nominally anti-Contimporanul and pro-Dada; Punct (editor was the socialist Scarlat Callimachi). This Dadaist-Constructivist journal also cultivated abstract lyricism.

In the newly founded Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (in December 1918), Zagreb played a particularly important role in connecting with Western centers and contributing to the quick modernization of life. Therefore it was not surprising that it was there that Zenit (Zenith), the international magazine for new art and culture appeared in February 1921. Zenit published manifestos declaring antimilitarism and brotherhood among nations; it was open to the international avant-garde scene (this character of the review was ensured by the French-German writer Yvan Goll who was co-editor of Zenit in 1921–22, nos. 8–13). A great number of contributions came from almost all parts of the world, seeking absolute freedom, with an emphasis on liberated language and poetry (words in freedom, words in space), accepting all innovative, progressive ideas, forms of expression and stylistic differences.

In that respect, the founder and editor of the review Zenit, Ljubomir Micić, in the beginning supported the international Expressionist mood with works by Egon Schiele, Vilko Gecan, Jovan Bijelić, Mihailo S. Petrov etc. FIG. 6 Soon the Italian Futurist enthusiasm for dynamic movements and technological novelties also appears in Zenit with works by F.T. Marinetti, Buzzi, Depero, Azari. Nikola Tesla was celebrated as a genius-inventor. Simultaneously present was the Dadaist revolt, with its claim for the abolishment of traditional culture, old forms of expression and freedom for interpreting reality (Dragan Aleksić, Branko Ve Poliansky, and Hungarian Dadaists from Voïvodina). Zenit also included French Cubist Orphism and its research into formal structures and colors, materials and relations to music (Robert Delaunay, Serge Charchoune, Alexander Archipenko). Particularly successful was the collaboration with the Russian avant-garde from Berlin – the direct connections with Lazar El Lissitzky and Ilya Ehrenburg who edited the special Russian issue of Zenit, no. 17–18, October–November 1922) dedicated entirely to new Russian literature, plastic arts, theater, music etc. Zenit also supported early manifestations of Surrealism (around Paul Dermée and Max Jacob), and finally social commitment in culture (dissemination of statements from De Stijl, Bauhaus and Purism).

The Zenitist idiosyncrasy culminated with the slogan Balkanisation of Europe by means of a metaphoric figure Barbarogenius – coming from innocent, wild areas of the Balkans and ready to recover old, tired and degenerated Europe – responsible for the unprecedented tragedies and traumas of World War I. In that respect, Micić’s book AntiEurope shows a fundamental anti-European state of mind.

Two year later, in 1923, Micić had to move from Zagreb to Belgrade because of his radical and severe criticism of Croatia’s petit-bourgeois in culture and politics. But Belgrade was also not ready to accept his isolated behavior, sharp judgments and suspicious ideas published in Zenit and related to the Bolshevik Soviet Union. For various reasons, being subversive, critical, and autonomous, Micić was put on trial and the police banned Zenit editions on several occasions. Finally, because of the article Zenitism through the Prism of Marxism, signed by a certain “Dr. M. Rasinov”, obviously a fictional character (Zenit, no. 43, 1926), Micić was accused of organizing a Bolshevik Communist Revolution and coup d’état. This turned out to be the last issue of Zenit. Micić escaped to Paris and was back in Belgrade only ten years later, in 1937. His heroic years were almost forgotten and they so remained until his death in 1971.

To quote one example of the international position of Zenit in the 1920s: Ljubomir Micić’s program text “Zenitosophy or the Creative energy of Zenitism” (originally published in Zenit, nos. 26–33, 1924) was translated and printed in Der Sturm and Blok (September 1924), in 7Arts (March &April 1925), Het Overzicht (1925), and according to Micić in several other reviews (with no data).

One of the most important activities during the existence of the review Zenit was the First (and only) International Zenit Exhibition of New Art, inaugurated in one music school in Belgrade in April 1924. The best example of plastic ideas that Zenit disseminated was the work by Josip Seissel, in Zenitism called Jo Josif Klek. His system PaFaMa (Papier-Farben-Material), abstract paintings and temperas, his Dada and Constructivist collages and photomontages, were published in Zenit and exhibited in various shows as representative of Zenit. The other works exhibited and collected in the Zenit gallery first in Zagreb and also in Belgrade, came from eleven European countries and the United States, including Vassily Kandinsky, Alexander Archipenko, Robert Delaunay, László Moholy-Nagy, Lajos Tihanyi, El Lissitzky, Jozef Peeters, Albert Carel Willink, Albert Gleizes, Louis Lozowick, Serge Charchoune, Helen Grünhoff…and several Yugoslav artists (Mihailo S. Petrov, Jovan Bijelić, Vilko Gecan, Vjera Biller…). The stylistic variety of exhibits in this show was the deliberate indicator of pluralism that the review Zenit declared.

In Zagreb, in 1922, Dragan Aleksić, close associate of Micić’s, published his small but important reviews Dada Tank and Dada Jazz, trying to formulate Yugo-dada, following his interest in Dadaism awaken in Prague where he stayed with Micić’s brother, Branko Ve Poliansky (aka Branko Micić; called also Valerij Poljanski), a Zenitist poet, writer, editor and later painter. The answer came from Poliansky who immediately published his review Dada- Jok and Dada Express pamphlets/papers – defending Zenitist positions with Dadaist tools: criticism, sarcasm, irony, photomontages, new typography etc. Poliansky was also the editor of the proto-Zenitist reviews, published in Ljubljana in 1921/22 –Svetokret (Turning World) and Kinofon – the first review on cinema predicting the arrival of sound film. FIG. 7

Ananarchist poet Anton Podbevšek, author of the book Človek s bombami (Man with the Bombs, 1925) published in Ljubljana, was the only editor of the review Rdeči pilot (Red Pilot, 1922) and its Proletcult program. He inspired young generations with “cosmic anarchism” – ideas coming from Nietzsche, Whitman and social criticism. Some information and ideas also came from Micić and his review Zenit, as was the case with August Černigoj, a Bauhaus student, identified with Slovenian Constructivism, published in Der Strum in 1928. Černigoj’s exhibition in Ljubljana in 1925 was considered politically dangerous, and for that reason he had to leave the country. Back in Ljubljana from Trieste, together with Ferdo Delak he published three issues of the review Tank (1927) where basic Constructivism was amalgamated with Zenitist vocabulary, traces of Futurism, Proletarian theater of Enrico Prampolini and Erwin Piscator – freed from traditional literature narrative. FIG. 8

Another Slovenian poet and Marxist, Srečko Kosovel, leader of the avant-garde review Mladina [The Youth] represents a clear example of Constructivism in poetry, the so-called “velvet modernism” leading towards later proletarian social radicalism. He practiced constructions of poetic motives – montage of fragments, a kind of visual poetry avant-la-lettre in his collection of Integrali [Integrals]. Kosovel died very young, in 1926, and his work remained almost unknown until it was revalorized only in the late 1960s.

The geopolitical situation after World War I affected greatly artists all over the world, particularly in the territories of the newly founded states. Among other things, the Dusseldorf declaration in May 1922 proclaimed: “Art is a universal and real expression of creative energy, which can be used to organize the progress of mankind.” This stimulated the proliferation of collaboration and an upsurge in new ideas in culture and art, expressed in numerous reviews which served as the mediators of communication all over Europe and especially among Central European countries. These reviews contributed to the transformation of traditional forms of expression to modernist and avant-garde models, with a belief in creating new order and new societies. Obvious transformation occurred from various forms of Expressionism and Cubism, towards Dadaist and Constructivist international language. This was possible due to powerful personalities like Kassák, Uitz, Moholy-Nagy, Teige, Seiffert, Peiper, Strzemiʼnski, Kobro, Janco, Maxy, Milev, Micić, Poliansky, Černigoj…

Some Central European reviews were dominated by writers (Devětsil, Fronta, MA, Zenit, Vezni, Crescendo, Zwrotnica), others by plastic artists (Blok, Contimporanul), but all disciplines were included and great attentions was paid to interdisciplinary forms, to layout, to new typography and to reproductions of art works. Photography – artistic and from real life, posters, reportage, new media (picture-poems, picto-poetra, picture-architecture, PaFaMa, Bildarchitektur / Képarchitektúra) and advertising, as a new way of communication, were the organic part of all Central European reviews of the 1920s. In various ways music and particularly jazz was present in those avant-garde reviews, as well as film and radio, circus, architecture and applied or decorative arts.

Some periodicals put an accent on pre-modern values, national mythology and archetypal ethno-symbolic elements as eternal sources of creativity (Barbarogenius in Zenit; preexisting ethnicities and folklore in Vezni; Primordialism in Contimporanul, early Poetismus in Formists).

Along with a theoretical approach, most reviews organized practical events– conferences, discussions, soirées, literary circle, and huge, truly international exhibitions covering multiple tendencies and artists’ works from various countries (MA, Blok, Devětsil, Zenit, Contimporanul) in general public instead of professional spaces, as the official art institutions were bypassed. Some exhibitions had great success (Bazaar of Modern art or Contimporanul show), others (like Zenit) – were ignored or criticized.

Exhibits were not only art works but also ready-made objects – the arte-facts of life; new machine era and technology were included, as they were glorified in articles and poetry as well. Poetry spoke about everyday modern life, social crises and workers’ problems. The critical approach was supported by the presence of Charlie Chaplin and a leftist orientation throughout articles and images, poems, collages, photomontages and films with V. I. Lenin (Ma, Devětsil, ReD, Černigoj, Tank, Blok, Zenit). All the editors paid great attention to the new, modern and attractive graphic design of their reviews or journals, often full of irony and criticism.

Although being predominantly a masculine affair, Central European avant-garde reviews show the signs of the coming era with the new roles for women: we encounter many women either as prominent female artists (Katarzyna Kobro, Teresa Žarnower, Toyen, Ida Brauner, Milita Petrescu, Margarete Kubicka) or as companions and active members of avant-garde societies, circles and reviews (Neil Walden, Jolan Simon, Ljubov Kozincova Ehrenburg, Lucia Moholy, Erzsébet Kassák Ujváry, Anuška Micić – Nina-Naj, Mela Maxy, Lilia Milev). And we discover some forgotten names and their works, vanished with the flow of history (Thea Černigoj, Vjera Biller, Helen Grünhoff /Elena Gringova).

The contacts among the editors were intense and constant: they exchanged letters, opinions, ideas, materials for reviews and magazines, for exhibitions and collections.

The destiny of each review was, as usual, very distinct: some were banned; some survived difficult times and were transformed according to new demands of new times. Some faded away gradually from the scene together with their founders and leaders. Some have accomplished their historical objectives, some have just tried to. The story goes on… but the traces of those heroic times remarkably remain and always invite new research and new interpretations.

References and Sources

Andel, Jaroslav. “The Constructivist Entanglement: Art into Politics, Politics into Art”. In Jaroslav Andel et al., Art into Life: Russian Constructivism 1914–1932, 228–230. New York: Rizzoli, 1990. [Exhibition catalogue.]

Benson, Timothy O. “Introduction”. In Central European Avant-gardes: Exchange and Transformation, 1910–1930, edited by Timothy O. Benson, 12–21. Los Angeles: County Museum of Art; Cambridge, Mass.–London, England: The MIT Press, 2002.

Botar, Oliver A. I. “From the Avant-garde to »Proletarian Art«: The Émigré Hungarian Journals Egység and Akasztott Ember, 1922–23”. Art Journal 52, No. 1 (1993): 34–45. [Online]. Available at: Academia.edu http://www.academia.edu/10993842/From_the_Avant-Garde_to_Proletarian_Art_The_Emigre_Hungarian_Journals_Egyseg_and_Akasztott_Ember_1922-23. [Accessed 5 June 2017].

Cârneci, Magda, ed. Bucharest in the 20s–40s between Avant-garde and Modernism. Bucharest: Simetria, 1994. [Exhibition catalogue.]

Dluhosch, Eric and Rostislav Švácha, eds. Karel Teige: L’Enfant Terrible of the Czech Modernist Avant-Garde. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999.

Genova, Irina. “Manifestations of Modernisms in Bulgaria after World War I.: The »Traffic« of images in the avant-garde Magazines – the Participation of Bulgarian Magazines from the 1920s”. In Irina Genova, Modern art in Bulgaria: First Histories and Present Narratives Beyond the Paradigm of Modernity, 203–214. Sofia: New Bulgarian University, 2013.

Голубовић, Видосава и Ирина Суботић. Зенит 1921–1926. Београд: Народна библиотека Србије, Институт за књижевност и уметност in assoc. with Загреб: СКД Просвјета, 2008. (Golubović, Vidosava and Irina Subotić. Zenit 1921–1926. Beograd: Narodna biblioteka Srbije, Institut za književnost i umetnost, in assoc. with Zagreb: SKD Prosvjeta, 2008.)

Кирова, Лилија. „Антитрадиционализам периодике у Бугарској и Србији у доба модернизма”. In Српска авангарда у периодици: Зборник радова, ед. Видосава Голубовић и Синиша Тутњевић, 357–366. Београд–Нови Сад: Институт за књижевност и уметност–Матица српска, 1996. (Kirova, Lilia. “Antitraditionalism of periodicals in Bulgaria and Serbia in the period of Modernism”. In Serbian Avant-garde in periodicals: Collective volume, eds. Vidosava Golubović and Staniša Tutnjević, 357–366. Belgrade– Novi Sad: Institute for Literature and Art–Matica srpska, 1996).

Kłak, Tadeusz, Czasopisma awangardy. 2 Vols. Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1978.

Košćević, Želimir. Tendencije avangarde u hrvatskoj modernoj umjetnosti 1919–1941 [Avant-garde Tendencies in modern Croatian art 1919–1941]. Zagreb: Galerija suvremene umjetnosti, 1982. [Exhibition catalogue.]

Krečič, Peter. Slovenski konstruktivizem in njegovi europski okviri [Slovenian Constructivism and its European frames]. Maribor: Založba Obzorja, 1989.

Passuth, Krisztina. Les Avant-Gardes de l’Europe Centrale, 1907–1927. Paris: Flammarion, 1988.

Piotrowski, Piotr. “Modernity and Nationalism: Avant-garde art and Polish Independence, 1912–1922”. In Central European Avant-gardes: Exchange and Transformation, 1910–1930, edited by Timothy O. Benson, 312–326. Los Angeles: County Museum of Art; Cambridge, Mass.–London, England: The MIT Press, 2002.

Steneberg, Eberhard. Russische Kunst Berlin 1919–1932. Berlin: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst, 1969.

Subotić, Irina. »Prilog proučavanju avangardnih pojava u Bugarskoj« [Contribution to the research of the avant-garde phenomena in Bulgaria]. Polja 299, January (1984): 19–20. A version of the same text: Суботич, Ирина. »Сотрудничеството на списаніе Зенит с българските художници« [The Collaboration of the Review Zenit with Bulgarian Artists]. Изкуство 36, 3 (1986): 7–14.

Švácha, Rostislav, ed. Devětsil: The Czech Avant-garde of the 1920s and 30s. Oxford–London: Museum of Modern Art–Design Museum, 1990. [Exhibition catalogue.]

Szabó, Júlia and Krisztina Passuth. The Hungarian Аvant–garde: The Еight and the Аctivists. London: Hayward Gallery, 1980. [Еxhibition catalogue, February 27 to April 7.]

Szabó Júlia. A magyar aktivizmus művészete, 1915–1927. Budapest: Corvina Kiadó, 1981.

Tank! Slovenska zgodovinska avantgarda [Slovenian historical Avant-garde]. Ljubljana: Moderna galerija, 1998. [Exhibition catalogue.]

Turowski, Andrzej. Existe-t-il un art de l’Europe de l’Est? Utopie & Idéologie. Penser l’Espace. Paris: Editions de la Villette, 1986.

Turowski, Andrzej, 2002. “The Phenomenon of Blurring”. In Central European Avant-gardes: Exchange and Transformation, 1910–1930, edited by Timothy O. Benson, 362–373. Los Angeles: County Museum of Art; Cambridge, Mass.–London, England: The MIT Press, 2002.

Vanci-Perahim, Marina. Le Concept de modernisme et d’avant-garde dans l’art roumain entre les deux guerre. Paris: Ecole pratique des Hautes Etudes, 1972. [Thèse de doctorat.]

Vlasiu, Ioana. “Bucharest”. In Central European Avant-gardes: Exchange and Transformation, 1910–1930, edited by Timothy O. Benson, 247–256. Los Angeles: County Museum of Art; Cambridge, Mass.–London, England: The MIT Press, 2002.

Vrečko, Janez. Slovenska zgodovinska avantgarda in zenitizem [Slovenian historical Avant-garde and Zenitism]. Maribor: Znamenja, Založba Obzorja, 1986.

List of Illustrations

Fig. 1. MA, Vienna, 1924. Cover design by Lajos Kassák

Fig. 2. Devětsil, Prague, 1922

Fig. 3. Blok, Warsaw, no. 5, 1924. Cover Teresa Žarnowerówna

Fig. 4. Contimporanul, Bucharest, nos. 50–51, 1924

Fig. 5. Crescendo, Yambol, no. 2, 1922

Fig. 6. Zenit, Zagreb-Belgrade, nos. 17–18, 1922. Cover design by Lazar El Lissitzky

Fig. 7. Kinofon, Ljubljana, no. 2, 1922. Cover design by Valerij Poljanski/Branko Ve Poliansky

Fig. 8. Tank, Ljubljana, no. 1 ½, 1926. Cover design by August Černigoj

All reproductions belong to the private archive of Irina Subotić.

- 1: Andrzej Turowski, Existe-t-il un art de l’Europe de l’Est? Utopie & Idéologie. Penser l’Espace. (Paris: Editions de la Villette, 1986).

- 2: Krisztina Passuth, Les Avant-Gardes de l’Europe Centrale, 1907–1927 (Paris: Flammarion, 1988).

- 3: Timothy O. Benson, “Introduction”, in Central European Avant-gardes: Exchange and Transformation, 1910–1930, ed. Timothy O. Benson, 12–21 (Los Angeles: County Museum of Art; Cambridge, Mass.–London, England: The MIT Press, 2002), 16, 21.

- 4: Oliver A. I. Botar, “From the Avant-garde to »Proletarian Art«: The Émigré Hungarian Journals Egység and Akasztott Ember, 1922–23”, Art Journal 52, No. 1 (1993): 34–45, 44, endnote 4. [Online]. Available at: Academia.edu http://www.academia.edu/10993842/From_the_Avant-Garde_to_Proletarian_Art_The_Emigre_Hungarian_Journals_Egyseg_and_Akasztott_Ember_1922-23. [Accessed 5 June 2017].