Context of the Performance in Theatre Culture

The absolute majority of Hungarians in Vojvodina live in villages and small towns.1 This is why the Hungarian-language theatres established in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia after the Second World War—first in the name of socialist popular education, and later purely to satisfy audience demand and increase ticket sales—moved out of their own buildings from the mid-1940s. The company of the Popular Theatre of Subotica (Szabadka), founded in the autumn of 1945, began its regional touring almost immediately, in January 1946.2 Although this was primarily a propaganda move and certainly a demonstration of the democratic nature of Yugoslav minority cultural policy, it undoubtedly had a significant impact on the life of the Hungarian community in Vojvodina.

Almost simultaneously, only 35 kilometres from Subotica, the County’s Hungarian Popular Theatre of Bačka Topola (Topolya), founded in 1949, began to tour and even surpassed the theatre of Subotica in popularity. The company regularly performed in the surrounding villages and on state estates. While in the second half of the 1950s they were seen by 6–8,000 spectators every year in their hometown and reached more than 20,000 people during their travels. In their last season, they had more than 37,000 spectators altogether.3 The County’s Hungarian Popular Theatre existed until 1959. At that time, according to the official justification, due to the reorganisation of the state administration system (i.e., the merging of certain counties), the company was merged with the company of Popular Theatre of Subotica,4 which could further strengthen its regional programme by creating entertaining performances that were specifically adapted to the needs of rural audiences and could be performed in parallel. Touring became more and more a part of the institution’s image, and it is no exaggeration to say that it was the theatre’s primary role until the end of the 1960s. At that time, approximately 430–450 performances were staged in a season (ten months). The vast majority of these were performed on rural stages and in community centres.5

Since, as far as we know, only four professional theatre-makers remained in Vojvodina (or returned there) after the Second World War,6 the professional companies of the Popular Theatre in Subotica and the County’s Hungarian Popular Theatre of Bačka Topola were, for decades, made up of the most talented amateur actors of the time, either through auditions or personal invitations by managers. Although few week-long courses in directing and acting had been offered since the 1950s, they were primarily aimed at training cultural workers in the countryside and not at developing the members of the theatre companies. The training of minority-language actors in the Federal Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, leading to a university degree, only began in 1974 with the opening of the Academy of Arts in Novi Sad (Újvidék).

The Grange Theatre (Tanyaszínház) was founded in 1978. Frigyes Kovács, one of the two founders, graduated that year from the first Hungarian-language drama department of the Academy of Arts in that year, and György Hernyák was the first Hungarian-language student of directing at the same institution. Both were of rural origin, first-generation intellectuals. In the summer of the same year, the Grange Theatre—certainly the first independent (semi-)professional minority theatre company in Yugoslavia—began its unique operation in the region. The basics have remained unchanged to this day. Every summer, the company regroups for a production, which, after a few weeks of rehearsals, is performed twenty-five to thirty times during a tour, lasting about a month and a half. Their performances take place in rural market squares, school playgrounds, pub yards, and football fields. After the applause, they dismantle the stage, take a rest, and in the morning continue on to the next village, where they start stage building again. Apart from the sound and lighting technicians, they have no technical staff to help them and no backup workers either. The actors build and paint sets, weld, do carpentry, sew costumes, and make wigs and props. The backbone of the company is made up of students of the Academy of Arts in Novi Sad, who are joined by professional actors on a voluntary basis and by invited amateurs.

A peculiarity of actor training in Vojvodina is that academy students must acquire the acting apparatus and behaviour required by the unusual playing conditions of the Grange Theatre very early on, in the summer following their first academic year.7 Moreover, each student will have the experience of living and making theatre in this creative community, which operates according to its own rules, and they experience coming into direct contact with the diverse but identity-sharing communities of their wider homeland during their annual tours.

Although, as we have seen above, touring was part of the practice of Hungarian-language theatres in the region in the mid-twentieth century, the young theatre-makers who founded the Grange Theatre were venturing into unexplored territory when they decided to perform in Hungarian villages in Northern Vojvodina, where no community centres or other community spaces for performances had ever been built and therefore had been avoided by professional companies. Thus, the aesthetic needs of the population of these small villages were unknown to the company. They offered their performances to audiences who had never before encountered any other form of theatre, and this had a decisive influence on their horizon of expectations and the way they received them.

In 1982, Angéla Csipak, the first dramaturg of the Grange Theatre, recalled the first five years of the company’s activities on the pages of the Híd periodical while self-reflexively analysing their own programming policy: “For a long time we believed that the only viable way, the psychologically absolutely valid method, was to educate the audience on the basis of the gradual principle; however, it is more likely that it was the most obvious, the easiest solution.”8 The dramaturg described a journey of experimentation and trial starting with the short scenes performed in the early years to Falstaff, which premiered in 1982 and was created from the first and second parts of William Shakespeare’s Henry IV and segments of the comedy The Merry Wives of Windsor.

Playing Shakespeare in the village dust had been an ideal of the company from the very beginning. In an interview in 1980, the leader of the company, Lajos Soltis already set the desired goal publicly: “We will get to Shakespeare!”9 Why it is the English author who became the company’s etalon is not entirely clear. If we look at the programmes of the professional theatres in Vojvodina that performed in Hungarian from their inception until the beginning of the 1980s, we can see that their repertoire hardly included any Shakespearean plays. The Novi Sad Theatre, founded in 1974, for example, did not play any of the author’s texts. Popular Theatre of Subotica had only six Shakespeare plays on its programme from 1945 to 1982 (The Taming of the Shrew, 1953; A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1955; Much Ado About Nothing, 1964; Richard II, 1971; Romeo and Juliet, 1976; The Tempest, 1980),10 and the County’s Hungarian Popular Theatre of Bačka Topola staged Hamlet in 1959.11 Endre Lévay, the founding editor-in-chief of the journal Híd, however, began his review of The Taming of the Shrew in 1953 by saying that “in any young theatre in the world, the appearance of Shakespeare on stage is a milestone in the development. Until the skill and artistry of the ensemble have approached these peaks, his works cannot be touched by untrained hands.” He called the playwright “the immortal of the spirit”, and described the first Hungarian Shakespeare performance in Vojvodina as a milestone, a celebration.12

Despite Lévay’s enthusiastic rhetoric, we cannot claim that the Shakespearean theatre aesthetics had a prominent place in the Hungarian-language theatre tradition of Vojvodina, but it is worth recognizing that the former Globe Theatre’s operation had many similarities with the Grange Theatre. The Elizabethan Era public theatres were also open to all who could afford to buy tickets. And buying tickets was not a major financial burden. The cheapest tickets could be bought for as little as a penny, the price of a quarter of a gallon of beer,13 and as a result the Globe’s audience was a representative cross-section of London’s population at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, from the footmen to the courtiers. And the performances were enjoyed by both men and women.14

From the very beginning, in addition to vertical social stratification, the audience of the Grange Theatre was also extremely diverse in terms of age. The free productions, which were accessible to all, are still attended by people of all ages, from very young children to the oldest inhabitants of the villages. It is therefore not surprising that the structure, thematic, and atmospheric richness of the productions are closely related to the Shakespeare productions of the former Globe. They are a good blend of impish comedy and philosophical, lyrical sublimity.

Dramatic text, dramaturgy

Angéla Csipak’s adaptation utterly simplified the explicitly complex plot of the two-part history play. Csipak removed several characters (e.g., Lady Percy) and merged the remaining minor roles. Nevertheless, the production moved around twenty characters, so several actors played two roles. The scenes of the political (King Henry and his circle) and personal (Falstaff and his circle) threads, which ran in parallel, were emphatically separated, leaving the story extremely fragmented. In this way, the Falstaff scenes from the comedy The Merry Wives of Windsor were easily inserted into the extremely short episodes, thus reinforcing the comic thread. Csipak cut out almost every monologue about war plans and tactics. The passages describing political power relations were really simplified. Therefore, the rebellion of the English lords was probably only traceable to fans of 15th-century English history. Instead of a battlefield of noble intrigue, the production became a series of ironic etudes, often degenerating into barroom humour. The games of power were as obscurely distant from the common folk of the stage as Yugoslav party politics were for the performance’s village audience. Of the nobles, the only one who had a major role was Falstaff, the outsider, big eater, and drunken womaniser who became the central character of the adaptation. Critics, however, said that Lajos Soltis’s portrayal of the knight-errant turned him into a complex figure, an intelligent clown.15 The focus thus shifted from the courtly people to the people of the inns, and the pub culture of mediaeval England took on a specific local flavour in Vojvodina.

Staging

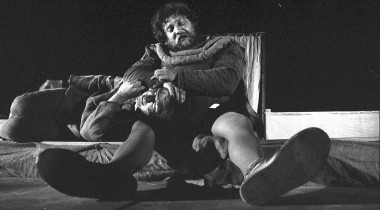

It is a surprising decision that, for the first time at the Grange Theatre, György Hernyák was not staging one of Shakespeare’s comedies, but rather one of the Bard’s less frequently performed plays. It is clear that he based his concept on the figure of the company’s iconic actor, Lajos Soltis. Hernyák created a distinctly fragmented performance. He separated the simplified scenes with emphatic darkness and drum rolls. In his review, literary critic Imre Bori compared Hernyák’s stage compositions to comic book panels.16 The director showed only what was absolutely necessary to understand the events as they unfolded, the conflicts as they took shape, and the opponents’ plans as they hatched. The clashes were the focus of his interest. As a result, there were only a few monologue scenes in the performance, and these were mostly spoken by the title character. His direction relied on the physicality and intense gestures of the performers. The knights wielded heavy axes and metal swords and protected themselves during duels with small round shields. Although these actions seemed genuinely risky, thanks to the well-rehearsed choreography, Hernyák left room for irony even in moments of heightened tension. The death of Henry Percy (Árpád Bakota) was more comic than tragic. Bakota took the murder weapon—Nándor Szilágyi’s (Prince Henry) longsword—under his arm and fell onto the stage. FIG 1

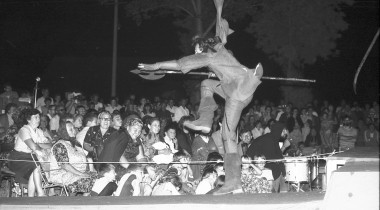

It is clear that for Hernyák the interactions of the lower classes were more important than the political games. In his production, he looked at the “great history” from a perspective familiar to the Hungarian villagers of Vojvodina. This way the profane layers of Shakespeare’s universe became dominant, which was underlined by the occasional unexpected appearance of bartenders, prostitutes, and drunks in the audience, who were happy to engage in loud and boisterous conversation with the spectators. For example, the drunken Pistol (Frigyes Kovács) asked some people, “Who are you?” The audience was asked to define themselves in relation to Shakespeare’s characters, and clearly, they identified most easily with Falstaff (Lajos Soltis) and his servant Bardolph (Levente Törköly), who ate roast chicken with fatty mouths, drank wine from huge goblets, and commented on the games of the powerful in the struggle for the throne with the apparent simplicity of folk wisdom. FIG 2 Two years after the death of Yugoslavia’s “eternal” president, Josip Broz Tito, this was the perspective of Hungarian viewers in Vojvodina.

Acting

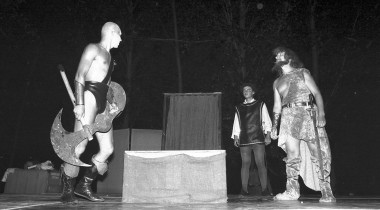

Compared to previous Grange Thetare performances, the monumental size of the stage allowed large entrences and the actors took advantage of this. They burst into the space with great energy. Often, they started from the back of the audience and ran onto the stage at an intense pace. FIG 3

The open-air conditions required the performers to replace the psychological-realistic gestures they were using in permanent theatres with more intensive—sometimes quite caricature-like—facial expression and movement. This, of course, went hand in hand with an increase in the volume of speech.

Imre Bori said in his review that, except for Lajos Soltis in the title role, the actors almost without exception played Shakespeare with ‘scholastic respect.’17 And although the characters speaking in the blank verse had indeed tried to portray the noble virtues in their sublime and the intriguing moments in their vile, they sometimes confounded the audience’s expectations with ironic gestures.

The language of the prose-speaking barmen, on the other hand, was very close to the audience’s own language. (István Vas’s translation was used.) In this familiar language, Soltis presented the wise-cracking, comic figure of the hero, who was long disillusioned with the power games of the great, as a complex personality with his own contradictions. His Falstaff was a down-to-earth character, emphatically subordinate to his body. He was at home among the common people but also capable of seeing and revealing the bigger picture. The nobleman was a similar character to the actor who portrayed him and who had been running the Grange Theatre since the previous year.

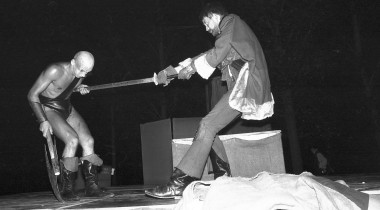

Among the performers in the crowds, the drunken Pistol (Frigyes Kovács) repeatedly engaged in conversation with the viewers, who were said to be eager to participate and answer his questions loudly and wittily.18 In this way, they became even more closely connected, even verbally, to the events on stage and the characters that took part in them. FIG 4

Stage design and sound

The action took place on a square plank stage, divided into two levels parallel to the audience. At the top, in the centre of the space, was a three-meter-wide, slab-shaped platform, about fifty centimetres high, covered on all sides with dark, rough poster. The sides of the stage structure facing the audience were also covered with dark material. Behind the platform was a door-width curtain, made of the same fabric as the backdrop, which served as a doorway for the scenes in closed rooms. Only King Henry and Prince Henry were allowed on the platform. Stairs led down from the front of the stage to the audience at either end. In the centre, there was a long, narrow plank connecting the stage and the ground level of the audience, who were arranged in a horseshoe shape around the playing area. The performance space was thus completely empty, except for the central platform and an occasional stool. The absence of back walls reinforced the familiar visual sights of the pre-determined spaces of the villages visited on the tour: there were corn fields, school and church buildings, tree-lined streets behind the Shakespearean figures, and the summer night sky of Vojvodina overhead. This solution was also reminiscent of the Globe Theatre in London, where the actors’ performances were framed by the details and decorations of the familiar building rather than by illusionary sets.

Although historicist intentions were completely alien from the set design, they were evident in the costumes. The actors wore hemp shirts, men’s trousers, full-length gowns and cloaks, leather boots and accessories, and even chainmail hauberks, which were of course more symbolic than historically authentic. Their colourful eclecticism, however, drew the audience’s attention to the actors’ gestures and the physicality of the performance. The appearance of Árpád Bakota, who played Henry Percy, was particularly iconic. He wore black leather boots and briefs with slings reminiscent of a wrestler’s singlet, revealing much of his otherwise naked body. His head was shaved bald and he held a huge battleaxe. FIG 5

There was no pre-recorded music during the performance, but the scenes were separated by darkness and an increasingly nervous drumbeat. Except for these pauses, white lights illuminated the stage and the audience.

Impact and posterity

Since the early 1980s the Grange Theatre has developed into a cultural movement. The company’s performances became key events in the life of rural communities, and often the most important village festivals and celebrations were organised around the company’s annual guest performances. The performances also provided an opportunity for representatives of other artistic disciplines to visit small Hungarian villages in Yugoslavia with their own artworks. In 1982, on the opening day in the village of Kavilo (Kavilló) an exhibition opened of photographs by the photographer Anna Lazukics,19 and the then 25-year-old Josef Nadj (Nagy József), who later became a world-famous dancer and choreographer, but at that time was studying at Marcel Marceau’s school in Paris, performed a solo dance etude.20 The fifth tour was also accompanied by the Forum Book Publishers’ book-selling van and the Hungarian and Serbian language press’s unceasing interest. The weekly newspaper Hét Nap published three reports on the tour’s stops, while the daily Magyar Szó published nineteen.21 In 1982, the short-lived Serbian company of Grange Theatre (Salaško Pozorište), led by the young Haris Pašović, was also founded. It lasted only one season and performed the fairy tale Johnny Peppercorn (Biberče) a few times in the sporadic Serbian area of northern Vojvodina, independently of the original Hungarian language company.

Although the first five years of the Grange Theatre’s work cannot be considered a closed period, the solutions that Falstaff clearly demonstrated are some the most striking features of a constantly evolving theatrical language that, with a few exceptions, still define the company’s productions. Similar to Elizabethan dramas, the Grange Theatre’s performances also combine character comedy, coarse, low-brow humour, and intellectual content. For this reason, the productions are often built up of loosely connected etudes, usually tied together by musical interludes or acoustic signs. It is also important that the performances often respond to contemporary public or political phenomena by using allegorical and metaphorical strategies.

Hernyák’s initiative did not start a renaissance of Shakespeare performances in Vojvodina, but after Falstaff, the Grange Theatre’s company staged three more of Shakespeare’s plays (A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1998; The Merry Wives of Windsor, 2003; Twelfth Night, or What You Will, 2011). These all being comedies is typical. Although Falstaff remains in the theatre maker’s memory as a great success and creative achievement, recent interviews with former spectators about the work of the company reveal that after the humorous performances of previous years, Shakespeare’s historical drama was received with bewilderment in 1982. The production was performed in 18 places and was seen by a total of 8,700 spectators.22

Details of the production

Title: Falstaff. Date of premiere: July 21, 1982. Venue:Kavilo. Director: György Hernyák. Author: William Shakespeare. Translator: István Vas. Adaptation: Angéla Csipak. Set designer: György Hernyák. Costume designer: Éva Pataki. Light technician: Rudolf Bálint. Sound technician: László Lakatos. Organizers: Irén Ábrahám, Angéla Csipak, László Törteli. Company: Company of the Grange Theatre. Actors: Valentin Venczel (Henry IV), Lajos Soltis (Falstaff), Nándor Szilágyi (Henry, Prince of Wales), László Törteli (Poins / Snare), Károly Keszég (Worcester), Árpád Bakota (Henry Percy / Lancester), Levente Törköly (Bardolph), Irén Ábrahám (Mistress Quickly), István Bicskei (Glendower), Péter Szedlár (Vernon), Frigyes Kovács (Blunt / Pistol), Elizabetta Bicskei (Dolly Tearsheet /Clarence), Dušan Polovina (Servant).

Bibliography

Bori Imre. “Shakespeare a tanyán.” Hét Nap, 6 August, 1982, 12.

Czérna Ágnes. Tanyaszínház: A harminc évad története (1978–2008). Novi Sad: Forum, 2009.

Csipak Angéla, “Ötéves a Tanyaszínház.” Híd 46, no. 9 (1982): 1072–1077.

Fischer-Lichte, Erika. “Színház az egész világ.” In Erika Fischer-Lichte, A dráma története, translated by Kiss Gabriella, 105–114. Pécs: Jelenkor, 2001.

Káich Katalin. A színész és a színjáték dicsérete: A szabadkai Népszínház magyar társulatának első 40 éve. Subotica: Életjel, 2016.

Lévay Endre. “Shakespeare-bemutató a szabadkai Népszínházban.” Híd 17, no. 4 (1953): 289–294.

Lovas Ildikó. “Interview with László Pataki.” Television of Vojvodina, 1993, 1. min. Accessed: 23.12.2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ucU2eB9GrHM&index=4&list=LL3hg_trHj-ogVjxyQqxjj_g&t=0s

Vida Daróczi Júlia. “Tanyaszínház másodszor.” Magyar Szó, 24 July, 1980, 12.

Virág Gábor sr. A topolyai Járási Magyar Népszínház, 1949–1959. Novi Sad: Forum, 2011.

Vukovics Géza and Gerold László. “A Suboticai Népszínház 20. évfordulója.” Magyar Szó, 31 October, 1965, 14.

- 1: The essay was written with the support of OTKA (PD 146626).

- 2: Vukovics Géza and Gerold László, “A Suboticai Népszínház 20. évfordulója,” Magyar Szó, 31 October, 1965, 14.

- 3: see Virág Gábor sr., A topolyai Járási Magyar Népszínház, 1949–1959 (Novi Sad: Forum, 2011).

- 4: Many recognised the systemic withering away of Hungarian culture in Yugoslavia behind this gesture of power.

- 5: Lovas Ildikó, “Interview with László Pataki,” Novi Sad Television, 1993, 1. min.

- 6: Sándor Sántha and Mihály Kunyi were actors, Rezső Nyáray was a director, and Béla Garay was an actor and director.

- 7: Sometimes years before they could step onto the stage of a permanent theater.

- 10: Káich Katalin. A színész és a színjáték dicsérete: A szabadkai Népszínház magyar társulatának első 40 éve (Subotica: Életjel, 2016), 181–190.

- 11: Virág, A topolyai Járási Magyar Népszínház, 128.

- 13: ~0,9 liter

- 14: Erika Fischer-Lichte, “Színház az egész világ,” in Erika Fischer-Lichte, A dráma története, trans. Kiss Gabriella, 105–114 (Pécs: Jelenkor, 2001).

- 15: Bori Imre, “Shakespeare a tanyán,” Hét Nap, 6 August, 1982, 12.

- 17: Ibid.

- 18: Czérna Ágnes, Tanyaszínház: A harminc évad története (1978–2008) (Novi Sad: Forum, 2009), 47.

- 19: The first female photo journalist of Yugoslavia.

- 20: During the tour, he performed the pantomime solo in Gornji breg (Felsőhegy) and Mali pesak (Kishomok) before the show. The promotional materials do not mention him as a pantomime artist, but refer to him as the “Parisian Rubber Man.”

- 21: Czérna, Tanyaszínház…, 199–200.

- 22: Ibid. 170.