Introduction

As You Like It was discovered relatively late in Hungary. Since the first performance in 1918 and the reprise of 1938, however, it has been one of the most popular plays and has had dozens of productions. In this paper, the focus will be on the productions of the period between 1949 and 1983, which is roughly equivalent to the period of communism and socialism in Hungary (1947–1989). The paper will offer a short analysis of the play, only focusing on the features relevant for this paper, and a historical summary to provide context for the productions analysed. The main interest is not in describing the productions of As You Like It, but in discovering Shakespeare’s comedy in a socialist context and seeing how Shakespeare was used in theatres and how acutely the productions reflected Hungarian reality in the age when they were produced. The four productions to be discussed are those of 1949, 1954-55, 1964, and 1983.

As You Like It and its brief history in Hungary

As You Like It is one of Shakespeare’s great comedies. It has been widely analysed by scholars;1 this section summarises very briefly the characteristics of the play that are relevant for this paper. The play is basically a love comedy, which explores different themes of love and, at the same time, offers a satirical commentary on them. “In this play, the plot includes several storylines, meanings are deeper, the language is denser and more complex, and imagery loses its decorative function and becomes an organic part of the plot”.2 As You Like It can also be seen as a political play exploring power relations,3 or a feminist play centred around Rosalinda and Celia.4 In terms of literary form, As You Like It is a poetic play; it notably lacks low comedy,5 and includes five full songs. These features may have made the play a natural choice for propagandists of the communist era. The political message is simplified into class struggle: “The civilised court is presented in an unfavourable light; it is a place where villainy, lust for power, and betrayal are daily practices, and where the purity and simplicity of nature is an attractive alternative with its goodness, equality, and happiness.”6 Impersonating Rosalinda’s and Celia’s characters is a great opportunity for young actresses, as they are stronger and more charming than most other heroines of Shakespeare’s. Despite this, the equality of sexes did not surface in the production discussed.

In Hungary, As You Like It was almost unknown until 1938. This may be due to the fact that the first good-quality translation was made in that year by Lőrinc Szabó (1900–1957), one of the greatest literary translators in Hungary, and the play was produced by the National Theatre in Budapest. In 1831, when the Hungarian Academy of Sciences first listed the Shakespearean plays worthy of translation, As You Like It was not included in the 22-piece list. It was considered a minor, insignificant play, not just in Hungary, but in Germany, too. The first Hungarian translation (by Jenő Rákosi) appeared in 1870; however, being a low-quality text, it did not contribute to the popularity of the play. The first performance in Hungary was held on 18 January 1918. The contemporary taste did not find the play interesting enough: “the play, compared to other works of Shakespeare, does not have a rich plot that unfolds from scene to scene and offers no suspense to the audience.”7 In the summer of 1938, Antal Németh, the director of the National Theatre, commissioned Lőrinc Szabó to make a new, modern translation of the play. The play, directed by Antal Németh, opened on 17 December 1938. The text was published in a small volume, then amended and republished in the 1948 Complete Dramatic Works of Shakespeare, a year before the first post-WW2 production. In 1954, Lőrinc Szabó reviewed his own translation again, so the radio broadcast of 1954 and the production of the so-called National Village Theatre (Állami Faluszínház) in 1954-55 featured a slightly retouched, improved text, which was published in the socialist Complete Shakespeare of 1955. Since the 1938 reprise, the play has been one of the most popular and frequently produced plays in Hungary, with a dozen productions in Budapest and about thirty outside the capital, with a new production every 3 or 4 years. A new translation was made in 2006 by Ádám Nádasdy.

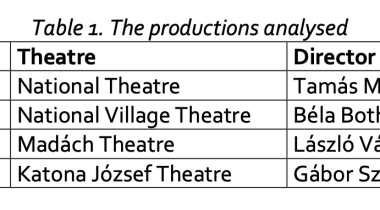

This paper examines the productions of 1949, 1954-55, 1964, and 1983 in Budapest on the basis of all available materials—recordings, if available, and theatre review8 —and puts each production against a historical context to understand how the age itself was present in the theatre and how the reviews reflected that presence. TABLE 1

The pre-socialist production of 1949

Hungary took part in WW2 on the wrong side. After severe bombing by the Western Allies, the front finally reached Hungary in late 1944. The Soviet Red Army seized the country from Nazi Germany (which had occupied the country in March 1944) in six months and gradually took control, using the Hungarian Communist Party, led by Mátyás Rákosi, as its local agent. After a few years of ailing democracy, communist leaders gradually established a Soviet-style government and adopted a Stalinist ideology. Between 1947 and 1949, all opposition voices were gradually silenced, and Hungary became a Stalinist dictatorship. The production of As You Like It in 1949 can be understood in this context: the happiness of the country after the end of the war, together with the dark clouds gathering over the countries occupied by the Soviet Union.

The directors of the production relied on the best actors and actresses of the period. Lajos Básti played a likeable, romantic Orlando, and Ági Mészáros’ Rosalinda was fresh and charming, a wise lady of the world; a critic noted that “no one else could play this role so well.”9 Zsuzsa Bánki was a kindly, over-earnest, and tender Celia, with very tasteful acting. Zoltán Makláry’s Touchstone was playfully wise and offhandedly sensible, while Miklós Gábor played Jaques with a lot of skill and dedication: he impersonated an eccentric, lonely traveller, “who chose the angry man, the indignant snarler” from the possible interpretations of the role.10

It is worth quoting a review by Dezső Kiss, who described the relevance of the play in the time of the production, and elaborated on the communist Shakespeare cult, which was, it seems, almost compulsory in the period between 1949 and 1955. The upbeat of the review is an anti-capitalist “the sun is now setting above Great Britain,” but then it quickly goes on to describe a new relationship between Shakespeare and the Hungarians: “It was not the old audience. The audience is now a cross-section of the new, workers’ society, all layers of society from government members to simple factory workers, and they were all charmed and elevated by the immortal genius.” Kiss adds that “the Shakespeare cult is unfolding powerfully from London to Moscow,” and now “Hungarian workers and young intellectuals are also part of it.” Theatres have the task of “giving a commentary on Shakespeare that fits the spiritual music of our time to the new Hungarian audience.”11 György Faludy, who also reviewed the performance, was more critical, perhaps alluding to the fact that the play was overly aimed at less literate audiences: in his opinion, “the text should have been given more respect and accompanied with acting and fun, instead of prioritising the acting.12

Most reviewers seemed to agree that As You Like It was a Shakespearean symphony of youth. This play is “sheer music, sheer melody, sheer fire, and young passion.”13 The play “can tell a lot to today’s people about a more natural, happy, and balanced life.”14 Probably this is close to what the directors intended to do: to provide some kind of youthful energy through Shakespeare’s comedy. The play was staged after Much Ado, Twelfth Night, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the greatest comedies, and now the focus was on social changes; while Hungarian society was changing very rapidly due to politically motivated terror, on the stage “social and cultural differences disappear in the utopia of the forest.”15 Aristocrats in Hungary were treated as parasites; noble titles and ranks were prohibited by law (from 1946); members of the former nobility were being intimidated, and their property was confiscated, so the picture of exiled aristocrats living peacefully in harmony with the people of the forest looks like distancing such problems into the Middle Ages. Another critic said that “life is shown as it is: the artful lies and intrigues of court life are in opposition with the natural purity and sobriety of simple and artless human life,”16 implying that the new Hungarian society of workers and peasants is better than the old one with its feudal-style class divisions.

In summary, it can be stated that the 1949 production was a popular, well-directed one, with good acting, and it already reflected the problems of the time: the opposition of the “poetic” and the “theatrical” Shakespeare,17 the coexistence of social classes, and the conflicts brought about by the forced social changes.

As You Like It during communist years

From 1950, all publishing houses and newspapers were nationalised, and official literary politics favoured Marxist aesthetics and criticism, which imposed serious limitations on the freedom of literature and developed a one-sided socialist norm that had a negative effect on authors, public education officials, and readers.18 The objectives of literature were also laid down in a five-year plan by Márton Horváth, the Communist politician who executed the party’s Stalinist cultural politics in the Rákosi era, and who was a chief promoter of voluntarist cultural politics, finally leading to general schematism, who wrote the following:

“The five-year plan determines the main directions and topics of our literature too. […] Democratic literature means literature that addresses millions, that is plain and of general interest. This is the literature of the new heroes of the people, living for the people. This is the new elevation, the literature of the pathos of building.”19

Knowing their value in educating people, communists nationalised all theatres between 1947 and 1949 and gave them generous subsidies. Their independence was taken away, the repertoire was set centrally and it mainly focused on harmless or progressive plays that would promote socialist culture. A new canon was prescribed, but this still included Shakespeare, who, by this time, was seen as a national classic and, at the same time, a true representative of internationalism.

“The new, complete Shakespeare aims at serving the cultural development of the Hungarian nation with weapons superior to the previous ones. Earlier, our bourgeois culture made significant progress in popularising Shakespeare, but, without a doubt, it is our people’s democracy that has made Shakespeare’s art available to broad masses of Hungarians. What would have been unimaginable 2-3 years ago is now undeniably real: besides our intelligentsia, masses of workers and peasants know and like Shakespeare, who is becoming a treasure of Hungarian folk art before our eyes. They know and like him—these words mean more than ever before; they mean that Shakespeare is seen as a revealer of the truth, a master of history and life, a teacher-poet.”20

Shakespeare was a rewarding author: his feelings against feudalism were seen as preoccupation with class struggle in a time when the Hungarian nobility suffered discrimination and deportation (this latter from 1951). His heroic fight against oppressive forces, his humanistic ideals, and his social “realism” were cheered by ideologists. As the only acceptable style of the period was Social Realism, Shakespeare was very often called a “realist,” with very little reason. Shakespearean heroes, to a certain extent, turned into predecessors of socialist heroes: people who acted and fought for their ideals.

Shakespeare’s comedies offer great entertainment for any audience. As staging political plays had proved too dangerous in the late 1940s and early 1950s, comedies were seen as beneficial in two ways: they offered innocent entertainment and relieved some of the tensions in the rapidly changing Hungarian society. Early productions, like Richard III in 1947, represented the triumph of socialism over fascism and worked very well with the public. When the play was staged again in 1955, in the worst years of communist terror, it turned politically subversive: the play’s resemblances to the realities of communist rule (terror, executions, intimidation, show trials, and, on the other hand, victorious propaganda. and self-adoration) struck a chord with audiences, who cheered for minutes on end, e.g., when the scribe arrived onstage with the prefabricated verdict.21 The 1950 production of Macbeth demonstrated the same. The stage was crowded with explicit signs of tyranny: armed guards and spiteful informers. In 1963, a critic finally admitted that this was interesting and topical then, “right after the fall of Fascism and in the years of the rigidifying personality cult.”22

In accordance with the official goal of educating people through Shakespeare, an adaptation of As You Like It was broadcast on radio in 1954,23 and the inclusion of the play into the repertoire of the so-called “National Village Theatre” (Állami Faluszínház), which had been established in 1951 to hold theatrical performances in villages and towns far from city theatres, was approved. The play was performed all over the country 182 times.24

The didactic nature of the performances was reflected in reviews, as if the reviewer had been watching the audience instead of the play. The critic György Vécsey said, for example, that “the faces of peasants, workers, and intellectuals equally reflect the joy of artistic experience.” He presumed that the director had decided which characters were valuable and which valueless and presented the play thus to the audience. “How well they [the audience] understand Touchstone’s witty remarks when he mocks the aristocracy!” he rejoiced.25 Jenő Zólyomi added that “there is a need for not the one smoke-screened in an aristocratic, bourgeois manner, but the real Shakespeare, who, through his writings, is always the advocate of the oppressed,”26

Mihály Barota thinks that the dominant topics of the play are social injustice and love games and shares the opinion that “As You Like It gives everybody something to think about, grieve, contemplate, take pleasure in, and cheer up with,”27 Both Zólyomi and Mrs. Szántó, however, focus on the social presence of the theatre itself and share a lot of information concerning organisation. Village Theatre is “an important cultural institution of our people’s democracy, which presents progressive Hungarian and foreign pieces to masses of people,” and also it is “a matchless cultural venture: it has given Shakespeare to the simple people of villages and hamlets,” and this proves that “the great playwright is of the people and for the people.”28 The greatest perspective of the blooming Shakespeare cult, he argues, is “when village people learn from this author;” “simple village people, thousands of our workers laugh, rejoice, and cry” when watching the play. He concludes that the performance was “a great event and a joyful day in the cultural life of the town.”29 Mrs. Szántó, a woman who was a member and functionary of the Party, reveals how hard it was sometimes to recruit an audience. She states that “the Village Theatre is known and liked in all our villages” and it is a pleasure that “people sometimes literally besiege the ticket office; moreover, in villages, extra seats have to be installed to seat the audience.” However, this is not true in Szombathely, which “has monthly performances with very low attendance,” so “we had to do laborious agitation work all week to succeed, but the result speaks for itself: the Great Hall of the County Council was full.”30

The writings presented above tell us about the enormous political forces put behind the Village Theatre and Shakespeare, who was seen as a teacher, and, consequently, people were seen as docile students. Still, the light-hearted acting and the inalienable value of As You Like It gave memorable moments to the public, and probably this was the main goal.

Socialist As You Like It after 1956

The worst years of hard-line communism lasted from 1950 to 1953, when the totalitarian state controlled almost everything, including literature and publishing. State terror, intimidation, executions, show trials, as well as famine and a brutal decline in living standards, were everyday realities. The death of Stalin in 1953 somewhat loosened the grip, and the ensuing events culminated in the Revolution of 1956 and Rákosi’s downfall. From 1957 on, János Kádár (1912–1989), the new socialist leader of the country,31 meticulously set up a unique political system in which citizens were emphatically asked to remain inactive in politics in return for a slightly higher standard of living. Balancing between the desires of the Hungarian people and dictates of the Soviet Union, Kádár gradually set up a fairly well-liveable political establishment, where “those who are not against us are with us.” This is what many people call “Goulash Communism” (although, officially, Hungary was a socialist country, and there was no more talk of communism after 1956), and this is what made Hungary “the Happiest Barrack” in the Socialist Bloc. To support his establishment, Kádár invented the cultural system of “Ban, Tolerate, Support” (in Hungarian these are referred to as the three T’s: Tilt, Tűr, Támogat). In such circumstances, art that was banned or tolerated was always more popular than officially supported art; artists and reviewers developed a form of doublespeak, which meant hinting at something without explicitly stating it, and required reading between the lines from audiences.

By 1964, the year of the next production in Budapest, the retaliations for the Revolution were over, order had been restored, the authority of the Party was reinforced, and people had begun to understand that socialism was to stay for a long time. To counterbalance this, the standard of living grew, modern flats were built, modern shops were opened, and Hungary began to produce buses, motorbikes, and television sets. Fashion also changed, and people had a chance to travel abroad. It was in such circumstances that Madách Theatre staged the play again. The play was very popular with the public, and somehow it represented the psyche of the nation, which balanced between a violent rejection of socialist politics and a happy embracement of higher standards of living. This balance is the basis of the Kádár Period, during which doublespeak was more and more frequently used to describe feelings and facts without police or officials sanctioning it, but with others understanding perfectly what one was talking about.

The production opened on 30 May 1964, featuring some of the best Hungarian actors. Rosalinda was played by Ilona Béres, who presented a charming, clever, cheeky girl who sees her exile as an adventure. She acted with irony, humour, and dignity, also incorporating some playful-fabular notes in her acting. Géza Tordy’s memorable Orlando was characterised by a simple acting approach, a mixture of courage and pure love. Celia (played by Csűrös Karola) was a bit demure but naughty and flirty girl. Jaques, played again by Miklós Gábor, was a contemplative character, characterised by whimsicality, mockery, and philosophy.32 János Körmendy’s Touchstone was colourful, tasteful, and cleverly built up. The set was a small hill in the middle of the stage, with ascent and descent for the characters to walk on, and curtains were used around the stage to provide background.

It is quite amazing to see how the reviews of the play reflected upon the present concerns of Hungary as well as the performance itself. One prominent feature is the presence of contrasting feelings. The unnamed reviewer of the periodical Köznevelés (Public Education) states at the very beginning of her/his paper that As You Like It is not real comedy, “the tragic chords can also be heard,” and that the play equally contains “weltschmerz, philosophism, and optimism.”33 Iván Sándor also emphasised that the play represented “both cheeriness and gloominess.”34 The idea of using Shakespeare for education was still there, but in a milder form compared to 1949 or 1954. The reviewer of Köznevelés recommended that teachers go and watch the play with their students, and later they discuss what they have seen.35

Pál Kürti’s rather political review gives a detailed treatise of contemporary Hungarian mood, using the production as an excuse to lament on current affairs. His language in the review is an excellent example of doublespeak. “The forest accepts an unlimited number of émigrés,” he says, adding that “in some hardly endurable moments of our lives, at least in imagination, everybody has already been an émigré,”36 hinting at the fact that 200,000 people left the country after the Revolution. Another example is, “Jaques followed the exiled Duke and his followers into their emigration, but he in fact represents what today we usually call ‘inward emigration’” (the term refers to an inward turning away from politics to somebody who does not accept the present ideology but does nothing to actively stop its spreading). When Kürti speaks about the usurping Duke and Charles, the wrestler, he marginally mentions that “dictators have used raw muscle force in all times,” obviously referring to Kádár (and maybe Khrushchev). Kürti is brilliant in this review: he almost explicitly speaks about Soviet imperialism and what we now call the Kádárian Restoration, knowing that he is perfectly covered by the play itself. When he says the forest-dwellers “get under the colonisation of the courtly émigrés [this might also refer to the Muscovite politicians, who had spent time in Moscow before returning to rule Hungary] and share the fate of developing countries” or “Adam’s speech airs all the suffering and sorrow of oppressed people,” he uses the clichés otherwise used in the Party press, applying them to the play and, obviously, Hungarian reality. And the last stab, obviously at Kádár, who had returned from Moscow on 5 November 1956 with clear orders to pacify the country: “the old Duke is a little scared when he hears he has to go back to the court; the émigrés are unwilling to give themselves to the numerous political complications of restoring an ancien regime.”37 Iván Sándor also explains the different modes of looking at contemporary reality: “the play does not conjure up what the naively simplifying eye can see about life; it shows more that which can be discovered only by people who know the simple secrets of life’s everyday naturalness.”38

In the 1970s, the deficiencies of the Eastern Bloc and Kádár’s system began to surface: enormous foreign debts, lack of innovation, and an impossibility of political self-expression, coupled with a fall in living standards, which drove many Hungarians into the private economy, where they literally worked themselves to death just to be able to afford a trip abroad, a car, or a refrigerator. People became disillusioned and uninterested, many turned to alcohol and other drugs. Secret services continued to spy and report on people. In the 1980s, the obvious failure of socialism started new, underground political movements in the country, but the average citizen, having been trained to rely on the government’s solutions, just became paralysed with fear of the future and lack of any hope to escape it. Soviet Premier Brezhnev died in 1982, and he was followed by an ageing and ailing Andropov, soon to die too (in 1984). Gerontocracy was taking over everywhere in the Eastern Bloc, and there seemed to be no future for socialism. Kádár was also disillusioned and weak, but he remained in office until spring 1988.

The 1983 production and its reviews, again, are clear references to the Hungarian state of affairs and uncover an understanding deeper than what is present in the official Party press. Katona József Theatre cast a brilliant young actress, Dorottya Udvaros, to play the role of Rosalinda. Her acting was hailed as “breathtakingly natural and ideally artistic,”39 it was characterised by “elemental charm, femininity, and disarming naturalness,”40 and her Rosalinda was “clever and engaging, attractive and self-confident.”41 Sándor Gáspár’s Orlando was a “naturbursch” type, pushy and timid at the same time; Ibolya Csonka’s Celia was carefully presented with a lot of inner humour. László Szacsvay’s Touchstone was a precisely sketched, classy court jester, comic and tragic at the same time. Miklós Benedek, one of the greatest actors at the time, played Jaques, with “more intriguing, militant bitterness than resigned melancholy,” and his great speech, All the world’s a stage… “was spoken with slightly less than hate.”42 Károly Eperjes, who played Silvius, can also be mentioned, as he had just started his career and was later to become one of the most popular actors in Hungary.

There are two minor themes the performance touches upon: alienation and resignation, both resonant to the realities of the 1980s in Hungary. Tamás Barabás stressed that “As You Like It stops a gap that comes from lack of emotions in our age.”43 Tamás Mészáros added that “everybody is suspicious and mistrustful,” and “the players exist in uncertainty and look for certainty in each other’s emotions.”44 But the main theme is lack of logic, motivation, and consequences: things just happen, and people just undergo them. As Mészáros puts it, in this play, Shakespeare “uses a ‘rabbit out of a hat’ type of dramatic mechanism to accidental, unpredictable, unexplainable events,” the plot lacks causes and consequences, all behaviour is unmotivated: “things happen and people simply accept them.”45 László Sinkó’s “Duke roams the open air with a shelter half on his shoulder; he never wonders anything, he never gets upset, as somebody who has realised that events are impenetrable and basically not important.” When they tell him he can regain his dukedom, he stoically heads home, “if it so happened.” This is how one would describe Hungarian society in the 1980s. In András Barta’s review, “the Duke receives the news with the impassive acquiescence of a seasoned politician.”46 This is how one would describe János Kádár at the end of his career.

“Where are the cloudless, fabular, bucolically idyllic performances of the 50s and 60s?” asks Barta, who describes the production along similar lines to Mészáros, saying we should not look for logic where there is none, and he thinks it is Jaques who shows us: “humans are at the mercy of their fellow humans and nature”, and accepting this “leads to fewer disappointments.”47 Jaques, however, also reminds us that “those who have experienced the atrocities of life so much should not so resignedly accept the handy appearances.”48 As You Like It, again, was a parallel to contemporary Hungary: the passiveness, helplessness, and bewilderment of people who cannot but accept their fate and watch events unfold without any chance of controlling them. The production ran until as late as 1987, which proves its immense popularity.

Conclusion

Before starting to write this essay, I was convinced there was not much to write about As You Like It in Hungary, and I was the most surprised to find that the play is probably the best material to describe the relationship between Hungary and Shakespeare against the context of ever-developing socialism. Shakespeare’s play lends itself to many interpretations, and those interpretations will summarise the age in which they were produced: the forced Shakespeare cult in 1949, the “democratisation” of Shakespeare and anti-aristocracy remarks in 1954, the mournful mood of 1964 together with the resignation to political passivity, and the feeling of affairs out of control as well as impending disaster in 1983, of which people could be no more than passive onlookers by then. Paradoxically, As You Like It is a Shakespearean comedy that shows us the tragic traits in Hungarian history exceptionally well.

Bibliography

Almási Miklós. “Bájos örömök – álruhában.” Népszabadság, March 25, 1983, 7.

Barabás Tamás. “Ahogy tetszik.” Esti Hírlap, February 28, 1983.

Barnaby, Andrew. “The Political Conscious of Shakespeare’s As You Like It.” Studies in English Literature 36, no. 2 (1996): 373–395. https://doi.org/10.2307/450954

Barota Mihály. “Ahogy tetszik.” Szabolcs-szatmári Néplap, Nyíregyháza, February 13, 1955.

Barta András. “Ahogy tetszik.” Magyar Nemzet, March 13, 1983.

Erdős Jenő. “Ahogy tetszik.” Kis Újság, June 14, 1949.

Faludy György. “Ahogy tetszik.” Népszava, June 14, 1949.

Gardner, Helen. “Let the Forest Judge.” In Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing and As You Like It, A Selection of Critical Essays, edited by J.R. Brown, 149–166. Houndmills: Palgrave Publishers, 1979. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139015257.008

Gough, Robert. A Good Comrade: János Kádár, Communism and Hungary. London: I. B. Tauris, 2006. https://doi.org/10.5040/9780755618750

Horváth Márton. “Író-diplomaták.” Szabad Nép, April 17, 1949.

Kardos László. “Shakespeare.” In Shakespeare, Összes Drámái, edited by Kéry László, 6 Vols. 1:7–60. Budapest: Új Magyar Könyvkiadó, 1955.

Kéry László. Shakespeare vígjátékai. Budapest: Gondolat Kiadó, 1964.

Keszi Imre. “Ahogy tetszik.” Szabad Nép, June 14, 1949.

Kiss Dezső. “Shakespeare 1949.” Haladás, June 13, 1949.

Kissné Földes Katalin. Az Állami Faluszínház műsora 1951–1958. Színháztörténeti füzetek 12. Budapest: Színháztudományi és Filmtudományi Intézet, Országos Színháztörténeti Múzeum, 1957.

Kürti Pál. “Ahogy tetszik.” Magyar Nemzet, June 10, 1964, 4.

Latham, Agnes. “As You Like It.” In William Shakespeare, As You Like It, edited by Agnes Latham, ix–xci. London: Methuen & Co, 1975.

Mátrai-Betegh Béla, “Macbeth: Shakespeare-felújítás a Nemzeti Színházban.” Magyar Nemzet, October 24, 1963, 4.

Mészáros Tamás. “Oly édes az élet?” Magyar Hírlap, March 5, 1983.

N.n. “Az Ahogy tetszik a Madách Színházban.” Köznevelés, July 9, 1964.514.

Oliver, H.J. “Introduction”. In William Shakespeare, As You Like It, edited by H.J. Oliver, 7–42. London: Penguin Books, 1968.

Sándor Iván. “Ahogy tetszik.” Film, Színház, Muzsika, no. 23 (1965): 4–5.

Schandl Veronika. Socialist Shakespeare Productions in Kádár-regime Hungary. Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2008.

Sebestyén Károly. Shakespeare: kora, élete, művei. Budapest: Rózsavölgyi és Társa kiadása, 1936.

Sowerby, Robin. William Shakespeare: As You Like It. York Notes Advanced Series. London: Pearson Education Limited, 1999.

Szántó Jenőné. “Shakespeare Vas megyében.” Tanácsok Lapja, October 25, 1954.

Szele Bálint. “Translating Shakespeare for the Hungarian Stage: Contemporary Perspectives.” AHEA: E-journal of the American Hungarian Educators Association, 6 (2013). accessed 27.11.2024. http://ahea.net/e-journal/volume-6-2013/19. https://doi.org/10.5195/ahea.2013.121

Takács Ferenc. „Utószó”. In William Shakespeare, Ahogy tetszik, translated by Szabó Lőrinc, 149–155. Budapest: Európa Könyvkiadó, 1980.

Turi András. “Ahogy tetszik.” Esti Szabad Szó, June 12, 1949.

Vajk Vera. “Ahogy tetszik.” Népszava, June 9, 1964, 2.

Vass László. “Független kritika az Ahogy tetszikről.” Független Magyarország, June 13, 1949.

Vasy Géza. „Hol zsarnokság van”: Az ötvenes évek és a magyar irodalom. Budapest: Mundus, 2005.

Vécsey György. “Shakespeare – Esztergomban.” Színház és Mozi, March 25, 1954.

Zólyomi Jenő. “Shakespeare Tolna megyében.” Tolnai Napló, November 11, 1954, 4.

- 1: e.g. Agnes Latham, “As You Like It,” in William Shakespeare, As You Like It, ed. Agnes Latham, ix–xci (London: Methuen & Co, 1975); H.J., Oliver, “Introduction,” in William Shakespeare, As You Like It, ed. H.J. Oliver, 7–42 (London: Penguin Books, 1968).

- 2: Kéry László, Shakespeare vígjátékai (Budapest: Gondolat Kiadó, 1964), 128.

- 3: Andrew Barnaby, “The Political Conscious of Shakespeare’s As You Like It,” Studies in English Literature 36, no 2 (1996): 373–395, 374.

- 4: Robin Sowerby, William Shakespeare: As You Like It, York Notes Advanced Series (London: Pearson Education Limited, 1999), 103.

- 5: Helen Gardner, “Let the Forest Judge,” in Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing and As You Like It, ed. J.R. Brown, A Selection of Critical Essays, 149–166 (Houndmills: Palgrave Publishers, 1979), 150.

- 6: Takács Ferenc, “Utószó,” in William Shakespeare, Ahogy tetszik, trans. Szabó Lőrinc, 149–155 (Budapest: Európa Könyvkiadó, 1980), 153.

- 7: Sebestyén Károly, Shakespeare: kora, élete, művei (Budapest: Rózsavölgyi és Társa kiadása, 1936), 175.

- 8: These reviews can be found at the Hungarian Theatre Museum and Institute (OSZMI) as newspaper cutouts, and some do not include page numbers.

- 9: Erdős Jenő, “Ahogy tetszik,” Kis Újság, June 14, 1949. All translations from Hungarian by the author.

- 10: Vass László, “Független kritika az Ahogy tetszikről,” Független Magyarország, June 13, 1949.

- 11: Kiss Dezső, “Shakespeare 1949,” Haladás, June 13, 1949.

- 12: Faludy György, “Ahogy tetszik,” Népszava, June 14, 1949.

- 13: Kiss Dezső, “Shakespeare…”

- 14: Vass László, “Független kritika…”

- 15: Keszi Imre, “Ahogy tetszik,” Szabad Nép, June 14, 1949.

- 16: Turi András, “Ahogy tetszik,” Esti Szabad Szó, June 12, 1949.

- 17: See also: Szele Bálint, “Translating Shakespeare for the Hungarian Stage: Contemporary Perspectives,” AHEA: E-journal of the American Hungarian Educators Association, 6 (2013).

- 18: Vasy Géza, „Hol zsarnokság van”: Az ötvenes évek és a magyar irodalom (Budapest: Mundus, 2005), 17.

- 19: Horváth Márton, “Író-diplomaták,” Szabad Nép, April 17, 1949.

- 20: Kardos László, “Shakespeare,” in Shakespeare, Összes Drámái, ed. Kéry László, 6 Vols. 1:7–60 (Budapest: Új Magyar Könyvkiadó, 1955), 57.

- 21: Schandl Veronika, Socialist Shakespeare Productions in Kádár-regime Hungary (Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2008), 17.

- 22: Mátrai-Betegh Béla, “Macbeth: Shakespeare-felújítás a Nemzeti Színházban,” Magyar Nemzet, October 24, 1963, 4.

- 23: More information about the broadcast: https://radiojatek.elte.hu/radiojatek/53652

- 24: Kissné Földes Katalin, Az Állami Faluszínház műsora 1951–1958, Színháztörténeti Füzetek 12 (Budapest: Színháztudományi és Filmtudományi Intézet, Országos Színháztörténeti Múzeum, 1957), 13.

- 25: Vécsey György, “Shakespeare – Esztergomban,” Színház és Mozi, March 25, 1954.

- 26: Zólyomi Jenő, “Shakespeare Tolna megyében,” Tolnai Napló, November 11, 1954, 4.

- 27: Barota Mihály, “Ahogy tetszik,” Szabolcs-szatmári Néplap, Nyíregyháza, February 13, 1955.

- 28: Zólyomi, “Shakespeare…,” 4.

- 29: Ibid.

- 30: Szántó Jenőné, “Shakespeare Vas megyében,” Tanácsok Lapja, October 25, 1954.

- 31: More about Kádár and his career: Robert Gough, A Good Comrade: János Kádár, Communism and Hungary (London: I. B. Tauris, 2006).

- 32: Vajk Vera, “Ahogy tetszik,” Népszava, June 9, 1964, 2.

- 33: N.n., “Az Ahogy tetszik a Madách Színházban,” Köznevelés, July 9, 1964, 514.

- 34: Sándor Iván, “Ahogy tetszik,” Film, Színház, Muzsika, no. 23 (1965): 4.

- 35: N.n., “Az Ahogy tetszik…,” 514.

- 36: Kürti Pál, “Ahogy tetszik,” Magyar Nemzet, June 10, 1964, 4.

- 37: Kürti Pál, “Ahogy tetszik,” 4.

- 38: Sándor Iván, “Ahogy tetszik,” Film, Színház, Muzsika, no 23 (1965): 5.

- 39: Almási Miklós, “Bájos örömök – álruhában,” Népszabadság, March 25, 1983, 7.

- 40: Mészáros Tamás, “Oly édes az élet?,” Magyar Hírlap, March 5, 1983.

- 41: Barta András, “Ahogy tetszik,” Magyar Nemzet, March 13, 1983.

- 42: Barabás Tamás, “Ahogy tetszik,” Esti Hírlap, February 28, 1983.

- 43: Ibid.

- 44: Mészáros, „Oly édes…”

- 45: Ibid.

- 46: Barta, “Ahogy tetszik.”

- 47: Ibid.

- 48: Mészáros, „Oly édes…”