Please reference this article as Theatron Vol. 15, No. 4. (2021): 20–29. (See the PDF file at the end of the Table of Contents.)

“It appears that in Moholy-Nagy’s native land the photogram is highly popular as a teaching material, while in the schools of our country it is marginal.” (Floris M. Neusüss)

1.

The genre of the photogram has been a hallmark of my whole career. I keep finding research areas and topics of interest for which I find the photogram to be the appropriate medium. There is also a good reason for my nearly complete avoidance of the camera in my works, so much so that my overall relationship to photography can well be characterized as cameraless. The “cameraless photograph” is a familiar term in contemporary international photo theory and includes all techniques whereby a trace is left on a photosensitive material without the use of a camera. Beyond attributing an image-making, representational capacity to photography, I find it important to consider its more abstract, philosophical roles. I also try to understand why the photogram engages my attention, since the technique has been exhaustively covered in theory and is rather limited in its visual possibilities. The photogram has a strong tradition in Hungary: it is firmly embedded in the traditions of modernism and the avantgarde. Yet, this medium means something else, something more to me: the photogram gives me a comprehensive and attractive option of all the medial components and senses that repel me in camera use. Being based on my own artistic and human experience, this may not match the experience of other artists or scholars.

I try to reposition the medium of the photogram by including considerations previously neglected in relevant scholarly work. Rather than merely supplementing modernist and (neo)avantgarde considerations, I try to elucidate what may (partly) account for this lack of emphasis. I need this repositioning, because I consider the photogram to be not only an autonomous medium, but a paradigmatic one, which goes beyond the meaning and significance of the cameraless. It makes the general category of cameraless photography more precise and, at the same time, it pushes against its own constraints to open up important possibilities. When I refer to photograms, I mean less a technique, visual art procedure, or visual world. For me, the photogram has the paradigmatic significance of direct imprinting, similarly to the imprint of paint-coated bodies on a plane or to three-dimensional casting in sculpture. FIG. 1 Although these are nearly timeless techniques, their “success” always depends on how well the artist manages to determine the parameters of the imprinting conditions in a way that suits the given society.

2.

There was a renewed interest in cameraless photography after the First World War. The War was sometimes considered ‘the war to end all wars’, and it led to the utopian promise of modern industrial progress.

László Moholy-Nagy considered light as the primary medium of art as opposed to painting and pigment. He saw light as the instrument of the future and believed that the man of the future had to develop an intimate relationship with it, in order to be able to meet the challenges of the 20th century. In his view, light was as basic a material for photography as sound was for music. For him photography was one of the ways to shape light in a creative way, and he considered the photogram-experiments as the first and most important stage along the path towards photography.As he pointed out:

“The photogramme, or camera-less record of forms produced by light, which embodies the unique nature of the photographic process, is the real key to photography. It allows us to capture the patterned interplay of light on a sheet of sensitised paper without recourse to any apparatus. The photogramme opens up perspectives of a hitherto wholly unknown morphosis governed by optical laws peculiar to itself. It is the most completely dematerialised medium which the new vision commands.”1

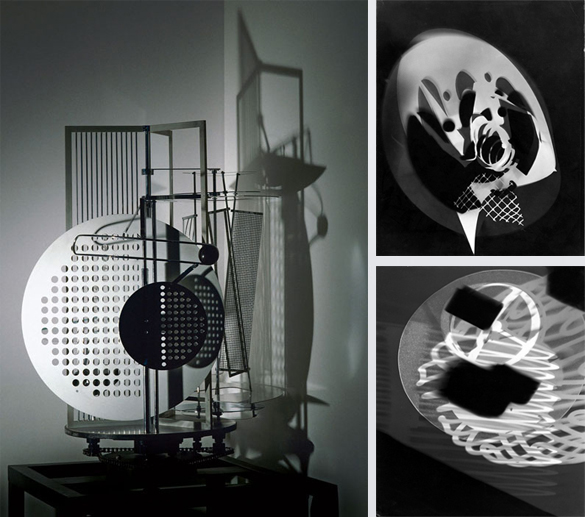

According to Moholy-Nagy, the photogram provides the key to acquiring abstract seeing. For him, abstraction was essential, as opposed to representation, and the photogram was the medium with an abstract capacity to shape light. It provided empirical visual data for a deeper understanding of light and space values. He created many of his photograms with the Light-Space-Modulator, which was a kinetic sculpture for generating light and motion effects. FIG. 2

“Moholy-Nagy used the term »photogram« instead of »shadowgraph«. He renamed it because he thought it was a better name: »I used or tried to use not alone shadows of solid and transparent and translucent objects but really light effects themselves.«”2

Moholy-Nagy made the photogram part of the introductory courses he held at the Bauhaus. He was also the most outspoken advocate of the integrated teaching of photography. However, Hannes Meyer, the new director after Walter Gropius, invited the photographer Walter Peterhans to teach photography as an independent, self-standing course at Bauhaus.

This was the first time when the fundamental difference between the two approaches to photography became clearly manifest, and not without conflicts. Gropius and Moholy-Nagy both left the Bauhaus in 1928. In one view, that of the Bauhaus’s new leaders, professional skills are indispensable for photography, it is a trade which has tricks and rules that can be taught. According to the other approach, here represented by Moholy-Nagy, imposing professional rules impairs creative thinking. As he wrote:

“The enemy of photography is the convention, the fixed rules of the »how-to-do«. The salvation of photography comes from the experiment. The experimenter has no preconceived idea about photography. He does not believe that photography is only as it is known today, the exact repetition and rendering of the customary vision. He does not think that photographic mistakes should be avoided since they are usually »mistakes« only from the routine angle of the historic development. He dares to call »photography« all the results which can be achieved with photographic means with camera or without.”3

3.

With the intention to pass on tradition, classify and identify laws and regularities, Dóra Maurer, a highly influential artist-teacher in the past several decades, used the photogram in the spirit of Moholy-Nagy. Her book titled Fényelvtan [On the Principles of Light] is the only detailed and comprehensive work on the subject in Hungarian. FIG. 3 Here she proposes the following definition:

“The photogram is an image produced without the mediation of a camera and photonegative, using solely light, photosensitive materials, and chemicals that develop the changes in those material, recording mostly the shadows of objects.”4

An essential difference between her photogram definition and Moholy-Nagy’s is that she calls the shapes appearing on the photosensitive surface ‘shadows’. In other words, Maurer adopts a different approach to abstraction, a characteristic feature of the photogram. It is not only in Maurer’s view of the photogram that the shadow has more significance than in Moholy-Nagy’s theory, but also in her visual education program.

Drawing shadows was an important part of the workshops she held in a cultural centre in 1975 and ’76 – together with Miklós Erdély, who was the most important figure in the neo-avantgarde scene in Hungary. In the beginning, Maurer would have preferred to leave drawing out of the programme altogether, as it was related strongly to the tradition of representation. For Maurer, it was a new experience that drawing, instead of being a form of representation, functioned as a diagram of interactions, leading back to abstract thinking. The drawing exercises primarily had a psychological / performative function. The focus was not on recording a view but in living a situation. Maurer began to use the photogram only at a later stage in her teaching practice. In 1981, she held an experimental course at the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest that focused on experimental photography and film. FIG. 4 It started with drawing shadows, a preliminary exercise in preparation to making photograms.

A photogram is a diagram of making images. As Maurer says:

“Photo-graphy (light imaging) broken down to its constituting parts totally revaluates traditional image making because every image documents its own birth at the same time. […] The image is no other than an authentic print of the process, and as such, it serves cognition.”5

In Maurer’s view, there is a straight line leading from the photogram and the creative use of the materials of the photogram to the methods of leaving marks in graphics. According to her the photogram can be regarded as the ancient formula of representation: the shadow and the trace of presence, these two are the origins of the image. She also declares that the differences between the fine artistic and photographic thinking can be grasped in the photogram.

“Professional photographers do not regard making photograms as a serious task. Meanwhile, artists, who are used to the freedom of shaping and forming, hold the photogram in respect because it does not depict what is visible to the eye.”6

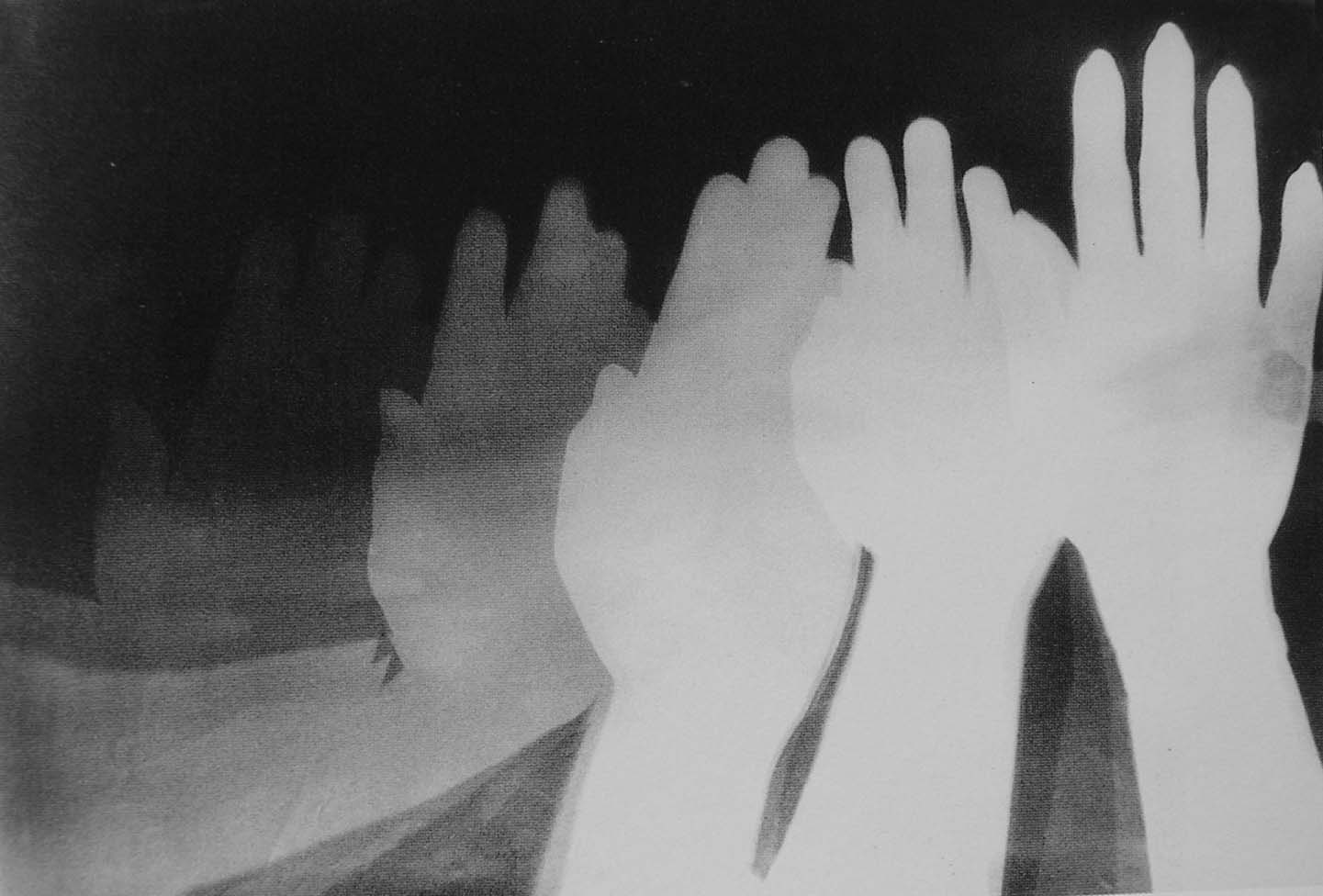

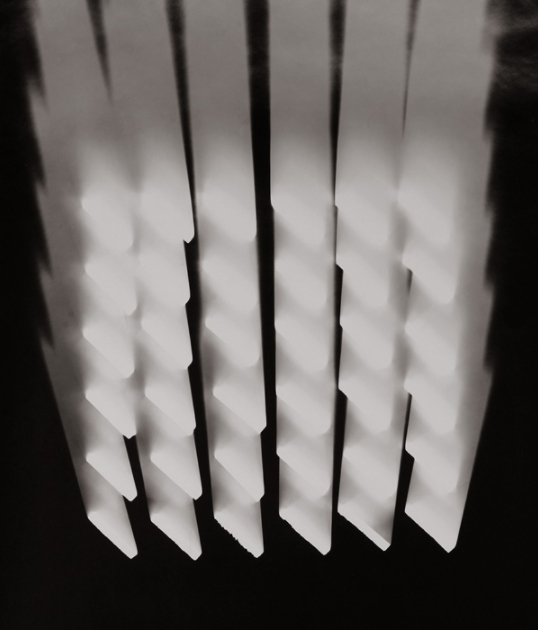

Despite all that, Maurer did not make many photograms. In fact, she made only two major series, Floodgates in 1977–78; FIG. 5 and Blind Touching FIG. 6 in 1984. Meanwhile she regularly used this medium in her teaching. Apart from historical examples, most of the images in her book are the works of students.

In 1987, Maurer taught an experimental seminar on the photogram at the Hungarian University of Arts and Design. I participated in that seminar as one of the five students at the Photography Department of the University. The method she proposed was not to force us to achieve artworks. Instead, she suggested that we try to be modest and explore all the technical potentials of the photogram. Not to strive to make art but to take the opposite approach: “invest ourselves in making something, and as we do so, something that is perhaps art may also come out.”7 The method proved effective. The seminar provided materials for Maurer’s book titled Fényelvtan.

4.

In the avantgarde and neo-avantgarde the photogram was seen as a democratic instrument. It was simple to make, it did not require either complicated equipment, or professional skills. The basic photographic tools were easy to access, lots of people had photo laboratories in the bathroom at home, and amateur photo workshops were also very popular. Compared to the technical skills and knowledge required for photography, the photogram was a means to achieve quick and spectacular results for those who did not possess those skills and knowledge. As a result, the photogram used to play a significant role in artistic education and training. The case today is different. The entire process is becoming more and more expensive and distant. The photogram is rather a “creative” technique than a handy tool. Though it is an element in almost every course on photography, its function is about gaining some darkroom experience. But the avant-garde practice of making photograms exemplify a unique stance where one can make an imprint of light without any camera, or virtually any instrument. This approach still can be used effectively in teaching and was an essential part of Moholy-Nagy’s and Maurer’s educational practice. Following them I also use this approach in my teaching practice. In the last years, I held workshops for groups of students at the Hungarian University of Theatre and Film. The participants of the class were to become actors and dramaturgs. The courses focused on space, light and explored how light and shadow can shape space values. In this sense, we went back to Moholy-Nagy’s concepts. We made use of the fact thatthe walls of the room were painted black. The students were drawing shadows on the black wall with white chalk that evoked reverse light and shadow relations, positive-negative states. A fundamental, medial feature of the photogram is that it treats the outcome’s negative tonal position as final result, with all its subversive connotations and consequences. FIG. 7 Thus the students inthe course were experiencing and experimenting with the visual characteristics of the photogram – without making photograms in effect.

Today, digital photography is a democratic medium accessible to anyone. Working in a darkroom is more of a privilege for visual art students and photographers. Nevertheless, I still feel it appropriate to call the photogram a democratic medium. The photogram by nature does not obey the rules of central perspective and single viewpoint, following from the medium’s practice and technical conditions. It is a significant feature of the photogram that the shadow of the three-dimensional object placed on the photoactive paper does not submit itself to the constraining rules of central perspective, the viewing from an external viewpoint. The deconstruction of the principle of the single viewpoint metaphorically inspired several theories over the past decades – but the photogram is the only technical medium that, by its immanent nature, possesses this anti-hierarchical extra meaning.

I would also recommend distinguishing within the photographic medium between camera-based and cameraless images. In case we consider photogram as an independent medium within photography, photogram might appear as a pendant of photography, as a social metaphor.

As Geoffrey Batchen put it in his new book about The Art of Cameraless Photography:

“Many artists now see modernism as an unfulfilled project and seek to reinvigorate its promise of a link between radical perspectives and social transformation. Their cameraless photographs therefore look back in order to signify a future that never was but still might be.”8

Bibliography

Batchen, Geoffrey. Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph. New York: Prestel Verlag, 2016.

Eperjesi Ágnes. “Expanded Photogram”. In Eperjesi Ágnes, Early Photogaphic Works, 7–19. Budapest: acb Research Lab, 2019.

Eperjesi Ágnes. “A fotogram mint akart és akaratlan képzet” [Photogram as Willed and Unwilled Representation]. Jelenkor 60 (2017): 593–603.

Fiedler, Jeannine ed. Bauhaus. Königswinter: Könemann, 2006.

Kaplan, Louis. László Moholy-Nagy: Biographical Writings. Durham–London: Duke University Press, 1995.

Maurer Dóra és Gáyor Tibor. Maurer – Gáyor: Egy művészpár:

Maurer Dórával és Gáyor Tiborral a Győri Városi Művészeti Múzeumban nyílt kiállításuk alkalmából beszélget Kaszás Gábor. Exindex. 23 Nov 2001. http://exindex.hu/index.php?l=hu&page=3&id=205.

Maurer Dóra. Fényelvtan [On the Principles of Light]. Budapest: Magyar Fotográfiai Múzeum–Balassi Kiadó, 2001.

Moholy-Nagy László. A festéktől a fényig [From paint to light]. Bukarest: Kriterion, 1979

Moholy-Nagy, László. Telehor. 2 Vols. Zurich: Lars Müller Publishers. 2011.

Moholy-Nagy, László. Vision in Motion. Milwaukee: Wisconsin Cuneo Press, 1947.

Neusüss, Floris, M. Das Fotogram in der Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts. Köln: DuMont, 1990.

List of Illustrations

Fig. 1. Ágnes Eperjesi, Somersault, 1987, chemi-photogram, 100 x 200 cm

Fig. 2. László Moholy-Nagy, Light Space Modulator, 1930 and photograms created by using it

Fig. 3. Maurer, Dóra, Fényelvtan On the Principles of Light. MFM-Balassi, 2001

Fig. 4. Photogram created at the „Szak-közi” interdisciplinary course, 1981

Fig. 5. Dóra Maurer: Floodgate, (from the series of photographs and photograms), 1977–81, photogram, 65 × 49 cm

Fig. 6. Dóra Maurer: Blind Touching, 1984

Fig. 7. Workshop at the University of Theatre and Film, Budapest, 2008

- 1: László Moholy-Nagy, Telehor, 2 Vols. (Zurich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2011), 35.

- 2: Louis Kaplan, László Moholy-Nagy: Biographical Writings (Durham–London: Duke University Press, 1995), 48.

- 3: László Moholy-Nagy, Vision in Motion (Milwaukee: Wisconsin Cuneo Press, 1947), 197.

- 4: Maurer Dóra, Fényelvtan [On the Principles of Light] (Budapest: Magyar Fotográfiai Múzeum–Balassi Kiadó, 2001), 7.

- 5: Ibid. 219.

- 6: Ibid. 8.

- 7: Maurer Dóra és Gáyor Tibor, Maurer – Gáyor: Egy művészpár

Maurer Dórával és Gáyor Tiborral a Győri Városi Művészeti Múzeumban nyílt kiállításuk alkalmából beszélget Kaszás Gábor, Exindex, 23 Nov 2001, http://exindex.hu/index.php?l=hu&page=3&id=205. - 8: Geoffrey Batchen, Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph (New York: Prestel Verlag, 2016), 42.