Introduction1

The recent decades show a growth in international publications on the methodological challenges of archiving and researching event-based art.2 More specifically, several research projects aimed at examining the histories of performance and theatre in Central and Eastern Europe during the Cold War.3 Despite the productivity of the field, Hungarian art and theatre historiography still lacks a comprehensive overview of marginalized and non-official theatre practices under state socialist times, including questions on the dynamics of the first and second public spheres, the role of amateur theatre practices in socialist societies and their international networks, as well as methodological questions of handling various types of documents and other materials. Moreover, detecting the histories of Hungarian amateur theatres cannot be neglected if one would like to understand how the amateur movement interconnected with important experimental aesthetics and agents of nonconformist practices in the second public sphere. Thus, researching how amateur theatres were organized and controlled in the 1960s and 1970s can contribute to a more nuanced understanding of art and theatre practices in the Kádár regime, including the relation of theatre and pedagogy, cultural education and art, processes of surveillance and resistance, negotiation and networking, state approval and ban. In addition, it can also offer a more complex contextualization for researching theatre practices of the first public sphere, as well as for examining well-known experimental theatre collectives of the era, such as the Kassák House Studio and Apartment Theatre at Dohány Street, Orfeo Studio, or Kovács István Studio.

In the present essay, I will look at a specific type of amateur theatres of the 1960-70s, namely, the practices of university theatres. In the given era, there were a few highly influential university theatre collectives that were embedded in student communities from Faculties of Humanities or Social Sciences, such as the Universitas Collective at ELTE Eötvös Loránd University or the University Theatre at Szeged. However, my case study, focusing on the Szkéné Collective, which was situated within one of the most prestigious universities of technical sciences in Hungary, the Budapest University of Technology, presents a slightly different story. Further methodological challenges arise from the fact that Szkéné as an important institution of contemporary Hungarian independent theatre sphere is active to the present day, yet without a permanent collective. Therefore, first and foremost, it is inevitable to clarify the structural changes of the collective and the theatre space over the past six decades.

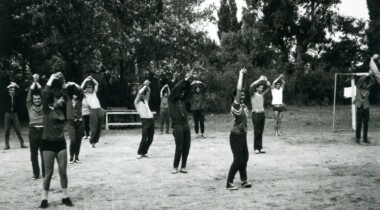

In 1961/62 the Budapest University of Technology initiated a student theatre, called the BME Literary Stage [BME Irodalmi Színpad] under the leadership of István Keleti, a prominent figure of amateur and youth theatre, later staff member of the Institute for People’s Cultural Education. The BME Literary Stage practically meant a more or less permanent collective with university students and external members who were either secondary school students or had civil jobs.4 In 1968 the collective was renamed Szkéné Collective [Szkéné Együttes],5 and in 1970 a permanent theatre space was built for the group on the second floor in building “K” of the Budapest University of Technology, which also got the name Szkéné Theatre [Szkéné Színház]. For almost five years, the Szkéné Collective remained the only permanent collective at Szkéné Theatre, and Keleti wanted to keep that structure.6 However, after Keleti left the collective in 1973 and Alfréd Wiegmann became the next leader of the group (until 1985), Szkéné started to change from a theatre with one permanent collective into a theatre institution housing more collectives, such as the renown BME Pantomime Theatre led by Pál Regős from 1975,7 as well as various national and international theatre, dance, and pantomime festivals, including International Pantomime Week in 1978, and later International Meeting of Physical Theatres between 1979 and 1992.8 Szkéné Theatre currently operates as a production house which invites various independent theatre groups and artists, offering space for rehearsals as well as productions. FIG. 1.

Most parts of the contemporary history of Szkéné Theatre are documented in official archives, such as the Hungarian Theatre Museum and Institute and the university’s own archive, and at the official website of the institution.9 The theatre celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in 2020 with a series of interviews with former and current artists of the theatre, including some former actors of the Szkéné Collective.10 However, we still know very little about the collective’s work between 1962 and 1973, as there is almost nothing to be found in the above-mentioned archives regarding this early era, and most probably as a consequence, these years have not been researched comprehensively. The amateur status of the collective can be seen as a reason behind the extremely low number of archived documents, as official theatre archives did not collect the materials of amateur groups in the 1960–70s as a principle. Amateurism as a uniformed interpretative frame influenced external as well as internal interpretation of the group’s work, resulting in an exclusion from theatre canons. Therefore, it is also important to clarify that amateur theatre in Hungary during this period mainly referred to the different structural conditions under which certain collectives operated, as opposed to state-approved and state-funded theatres, and the term did not necessarily refer to the quality of productions and performances. Moreover, experimental aesthetics rather characterized the works of amateur or alternative theatre groups. Theatre critic István Nánay suggested in one of his essays written in 1983 that while “amateur acting” [amatőr színjátszás] mainly referred to school and university collectives with the aim of public education and non-professional but valuable entertainment, whereas “amateur theatres” [amatőr színház] were associated with more professional goals with high-quality productions.11 Nevertheless, there are many examples when university collectives created aesthetically progressive, nonconformist, innovative productions. Thus, the terms “amateur”, “alternative”, and “experimental” were practically parts of the same scale.12

As a result, the story of the Szkéné Collective poses several relevant methodological questions for (theatre) historiography of the Kádár regime, including the accessibility of documents, leading and sometimes misleading narratives of historiography, and the emerging role of oral histories. On the one hand, we can see that edited volumes on Szkéné Theatre either strengthened a narrative that solely gravitates towards the pedagogical influence and importance of István Keleti,13 or barely touched the timeslot of the early 1970s in the history of the theatre.14 On the other hand, after conducting several oral history interviews with former participants of the Szkéné Collective – including Katalin Andai, Ilona Vercseg, László Böszörményi, Katalin Takács, and Éva Raffinger – it became clear that collective work and the power of community were major factors not only in the 1960s and 1970s, but even nowadays, when many of the members, now in their seventies, are still in an active and friendly relationship, supporting and meeting each other.15

In the following, therefore, my aim is to examine the dynamics of invisible and collective work, community creation, and the role of female participants and their work in the Szkéné Collective between 1962 and 1973. The hypothesis is that in order to acknowledge the role of community in amateur theatre practices, it is essential to readdress the hierarchical understanding of a leader/director and the group members, and to offer a narrative that is built on the usually hidden stories of collective creation, shared creativity and labour. Firstly, I will offer a short overview of theatre cultures and public spheres under the Kádár regime. Secondly, I will describe the challenges of researching the Szkéné Collective as an amateur theatre group, including the accessibility and characteristics of various archival sites and materials. Finally, I will offer an overview of narratives regarding the collective’s work, focusing on the performativity of historical evidence making, and possible means of integrating (hi)stories of community and collective creation. FIG. 2.

Theatre Cultures and Public Spheres in the 1960s and 1970s

During the Kádár regime (1956–1988)16 Hungarian theatre culture was influenced and formed by the nationalization of theatre institutions, which started in 1949. As a result, the operation of theatres was characterized by closely controlled programmes, staff, and productions: “The cultural politics of the Kádár regime, after the Rákosi era, were built on the principle of high-quality culture for the crowds, and while strongly supporting this vision, they also disproportionately controlled the field.”17 State control was carried out through partly political, partly administrative ways, and the main aim was to create a specific cultural content called socialist realist, as opposed to cosmopolitan anti-realist art.18 Theatres as public displays in Hungary meant important media for propagating the social changes proposed by the Soviet culture and party ideologies.19 From 1960 the Agitation and Propaganda Committee of the Central Committee of the Hungarian Socialist People’s Party was the official body which supervised the structure of theatre programmes and, if necessary, made changes to the season plans.20 In 1963, the Committee announced that the socialist content of theatres should be strengthened and a change in the methods of theatre management is needed.21 The socialist content of theatres would include the acting method loosely based on Stanislavski’s theories as well as an integration of Soviet playwrights into the dramatic canons.22

State control for theatres was provided through several national, municipal, and local institutions, which included the Executive Committees of Budapest and each County Councils, the Department of Cultural Management, the Agitation and Propaganda Committee, the Ministry of Culture, and the Theatre Arts Association.23 The amateur sphere was under the control of the Institute for People’s Cultural Education, which operated under the Ministry of Culture. In 1965, under the leadership of Imre Kiss, the institute created the Department of Art, Education and Research, which organized and managed the amateur sphere, meaning “non-professional, but state-recognized artists”.24 Apart from theatre collectives and literary stages, this area included film, photography, various forms of dance, and later puppet theatre, popular music, and youth theatre, however, church and classical music were considered forbidden categories.25 In 1971 the Department was divided into the Department of Visual Arts and the Department of Performing Arts. The latter supervised amateur theatres, youth and children theatre, puppet theatre, folk and contemporary dance, and they organized national festivals for amateur collectives in order to create a network of the initiatives. The above-mentioned István Keleti, leader of the BME Literary Stage and later Szkéné Collective, was working at the Department of Performing Arts from the 1960s, and also authored a methodological volume on the operation and working methods of literary stages and amateur theatre groups.26 Parallel to this, from 1957 the concept of the “3 T-s” in cultural politics (associated with György Aczél, the head of cultural management) categorized publicly shown and discussed artworks and art practices into three groups: to ban [tilt], to tolerate [tűr], and to support [támogat]. This framework, however, was not based on strict rules or laws, but rather on subjective opinions, and therefore, it initiated a negotiable network of special bargains based on individual political outreach and personal contacts.27

Controlled and supported theatres were parts of the so called first public domain “held together by an ideological project, the creation of a socialist consciousness”.28 The second public sphere included those actors, who, either willingly or unwillingly, for a long or a short time, were excluded from the first controlled sphere. The relation of the first and second public spheres was complementary, and not exclusive. As performance and art historian Katalin Cseh-Varga pointed out “the second public sphere required the first public sphere for its own existence. (…) Those who did not completely accept the first public sphere had the option of an escape route into the second public sphere, and vice versa: the second public sphere could not have existed without the observing eye of an ordered public sphere. The interplay of these two zones was inherent in the very dynamics of the public sphere under state socialism (…)”.29 The second public sphere offered more opportunities for autonomous communication and art practices, however, their venues and medial contexts had to be constantly re-created and re-formed, thanks to state bans, secret services, and police operation. Therefore, the second public sphere can be imagined as a fluid, continuously re-formed network of individuals, often artists without professional educational background, obtaining non-artistic civilian jobs.30 The venues of theatres operating in the second public sphere ranged from youth clubs and universities to culture houses and private homes. Alternative media platforms and strategies, such as samizdat publication or travelling private performances, defined the communication networks of this sphere.31 In addition, due to the consolidation of Kádár’s regime, during the 1960s some sort of cultural opening began in Hungary, which provided amateur and alternative theatres the opportunity to perform previously banned works and to experiment with theatrical forms.32

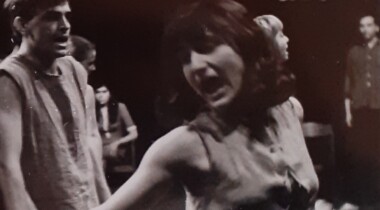

Within this context, university theatres experienced a relative freedom in the socialist society, partly because of the more relaxed rules enabling the collectives to visit various national and international festivals, and partly because of the less harsh censorship regarding their programmes, as opposed to those of established professional theatres. The operation and programmes of university theatres was usually supervised by the university councils and the university’s committees of Youth Communist League. The emergence of university collectives in the 1960s was fuelled by the success of the University Stage at ELTE Eötvös Loránd University [Egyetemi Színpad], which was established in 1957 with the intention of creating a shared cultural place for university students, where they could interact, become self-active, and create various artistic events.33 In the 1960s the University Stage functioned as a place of transition between state-approved and experimental artistic practices of the era by integrating actors from both sides, even those who had been officially silenced before. Moreover, it also became a place of international networking, and the Stage’s permanent group, the Universitas Collective was among the few that could travel to festivals not only in the Eastern Bloc, but also in Western Europe, including locations like Zagreb, Wroclaw, Birmingham, Parma, Nancy, Vienna, and Paris.34 Parallel to the Universitas’s work another important workshop started in Szeged at the Faculty of Humanities of József Attila University, which became an internationally recognized theatre for the 1970s. These leading collectives, together with a growing network of amateur groups, which was fostered by a series of national amateur festivals organized by the Institute for People’s Cultural Education, created an atmosphere in the 1960s and 1970s, which favoured the creation and establishment of university collectives in Hungary. FIG. 3.

Collective and Invisible Work at the Szkéné Collective

Art and performance historian Heike Roms pointed out in her influential essay Mind the Gaps: Evidencing Performance and Performing Evidence in Performance Art History that “evidence is not a thing but an event that is situated and mediated, and which relies on the co-creative presence of others”.35 Writing a history of the Szkéné Collective, therefore, would also demand methodological consciousness regarding already existing narratives and pieces of evidence in archives and collections. Although there are a few books mentioned above that tried to capture some parts of the collective’s history, their narration usually remained in a hierarchical disposition including István Keleti as an educator, leader and director and the rest of the group as young participants. As for the archival sites, the Hungarian Theatre Museum and Institute has very little materials on the first phase of the collective (two reviews, but no photos or playbills), however, the Budapest University of Technology’s own archive has some relevant materials on the structural operation of the collective in this period, including the fact that some members of the Cultural Committee of the university’s Youth Communist League, including second director and actor Tamás Varga and actor Ilona Vercseg, were active participants in the Szkéné Collective. In addition, the university’s newspaper, the Engineer of the Future [A Jövő Mérnöke] also gave frequent reports on the collective’s work and published interviews with some members. Some materials can be found in the Historical Archives of Hungarian State Security, which mentioned the leaders of the collective, usually in an affirmative context.36

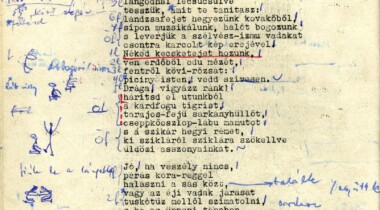

As a result of the relatively low number of materials in official archives regarding the group’s work between 1962 and 1973, detecting oral histories and personal archives proved to be essential in the research. Between June and November of 2022, I and Sára Ungvári conducted oral history interviews with former members Katalin Andai, Ilona Vercseg, László Böszörményi, Katalin Takács, and Éva Raffinger.37 Methodological challenges of drawing on living memory and testimonies arise from the collective work of evidence making, or, as Roms put it: “the constitution of evidence in such contexts is often the effect of complex interpersonal negotiations, even collaborations, which challenges the assumption that research is able to be detached objectively from either researcher or ‘researched’”.38 Accepting the fluid nature of interpersonal negotiations, there is a consequent need to return to certain events, topics, or practices during the interviews, in order to either challenge (mis)leading narratives, or to specify personal experiences. In addition to the interviews,39 materials in personal collections of former members Éva Raffinger and Péter Hidas also made a huge contribution to the research, including photos of rehearsals, summer camps and productions, playbills, promptbooks, and mails. These materials can promote an understanding of a clear change in the collective’s work: BME Literary Stage between 1962 and 1967 focused on producing events of poetry recitation with various thematic nodes, but from 1967 there was a conscious turn towards dramatic pieces, eventually leading to the oratorical aesthetics of the Szkéné Collective, which also characterized the opening of the theatre space in 1970. FIG. 4.

Examining leading narratives of the Szkéné Collective’s history, it is conspicuous that not only former members’ recollections strengthened the hierarchical status of István Keleti within the group, but also various reviews and essays written about the collective. For instance, theatre critic István Nánay, who is one of the very few experts that consistently followed the amateur and alternative theatre spheres from the 1960s, positioned Keleti in the middle of the Szkéné’s work in his 1986 comprehensive study on amateur theatres: “Before 1969 and for a while after it as well, István Keleti led the Szkéné Stage at the University of Technology. (…) Apart from literary events and Sándor Weöres’s oratory titled Theomachia, one of Keleti’s most matured piece was created at Szkéné (…)”.40 As a result, cultural memory often equalized the Szkéné Collective with Keleti’s pedagogical and directorial practices. Even personal interviews with former members confirmed that there was no real democratic decision making in the group: Keleti was an authority figure both on the structural and the aesthetic level.41 However, the interviews also challenged the image of Keleti as the only source of creative energy in the group.42 In the following, I will provide some cases that can highlight the dynamics of invisible labour both within and around the collective.

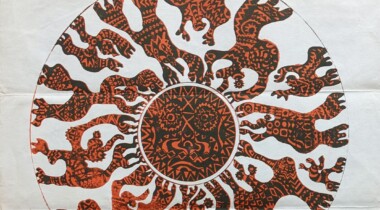

One of the most well-known and well-documented productions by the collective was Theomachia, which celebrated the opening of the theatre space on 21 March 1970. The production was based on the dramatic piece by Hungarian writer Sándor Weöres, inspired by ancient Greek tragedies. The characters of the play were divided into two categories: five gods (Okeanos, Gaia, Rhea, Typhon, and Zeus) and two choirs (one male, one female). The textual material fitted Keleti’s cultural ideas, which centred around the Greek and Roman mythology and humanistic education. On the visual and physical level, the production tried to grasp the conflict of the gods, who were reciting the text standing still on pillars, while the choir presented a dynamic physical language in the foreground. As former member, Katalin Takács, recalled, while the gods were speaking their parts, they were lit by a sharper light on the face and upper body, during which the choir was in the dark and communicating only through moans and murmurs.43 When members of the choir spoke their parts, often reciting the text collectively together, they were lit by a soft warm colour.44 The production was not only reviewed by the university’s paper, but professional theatre critics wrote about it in well-recognised theatre journals as well. FIG. 5.

All critics praised the physical language of the choir, highlighting it as the most innovative part of the production. In a 1970 essay on amateur theatre, theatre critic Péter Molnár Gál confronted the different styles of the main characters and choir members in Theomachia, underlining the importance of the latter:

“The choir operated through the principles of Grotowski’s theatre. The beauty of movements provided by the collective, an undecorated type of theatre which only wanted to shine in the beauty of the human body, powerful changes, and the actors’ style which was not based on identification but commentary: all of these provided a new experience, as well as dense and powerful effects. While the main roles were swimming in an emotional bulk of romantic amateurism, the dynamic, organized nature of the choir, their gymnastic actions, and focused, almost religious trance, and their increasing acting style from the quietest, whispering murmur to the loudest scream, promised the creation of a new theatre.”45

The overpraised aesthetics of the choir was usually evaluated as the result of Keleti’s directorial work, as another theatre critic, István Nánay, recalled: “The main strength of Keleti was his analytical and editorial skills. In Theomachia he understood that the text would die if a dozen young people had just recited it in different tones. Because of this, he formed groups and spatial shapes from human bodies, which interpreted the text. This was highly rare at that time.”46 FIG. 6.

In contrast with this narrative, the university’s newspaper gave a report on the summer camp at Balatonlelle in 1969, which preceded the premiere of Theomachia, and noted that it was Tamás Varga and Katalin Andai who were responsible for the movement of the choir.47 Andai confirmed this information during the personal interview and noted that in 1969 she, as a fresh student at the Theatre and Film Academy, gave physical trainings for the collective, and also designed the choreography for Theomachia together with Tamás Varga.48 However, as she also recalled, after the premiere only Tamás Varga’s name appeared in reviews as the choreographer.49 The cooperation was turned out to be even larger, as in another interview Éva Raffinger, who played the leader of the choir in the production, pointed out that she also contributed to the choreography, which seems no surprise, given the fact that Raffinger was trained to be a ballet dancer in her childhood. As these traces show, the most innovative part of Theomachia, namely, the choir’s unique choreography and physical language was the result of a cooperation, including (at least) three members, none of which was the director, Keleti himself. Out of the three co-operators, only one was given credit in the official reviews: Tamás Varga, who was said to be the other authority figure besides Keleti, and also the leader of the Cultural Committee at the university. The two other female members’ vital contribution to the creative innovation of movements was seemingly forgotten for a long time, and has not been credited in essays or reviews.

Apart from invisible creative labour, there was a considerable amount of invisible operational work as well in the history of the Szkéné Collective, which was left out of theatre histories. An eminent example was Judit Zigány, who was not an actor in the group, but said to be a mother figure for them, and although sometimes she fulfilled the tasks of a director’s assistant, she was remembered as the one responsible for catering during the summer camps in Balatonlelle and elsewhere.50 Furthermore, she also played a major role in organizing a trip to France in 1973, where the group presented two productions. And there was artist Ilona Harsay as well, who designed and fabricated the scenery and costumes of Theomachia, among others, and was also among the many forgotten creative figures of the group.51 Besides, relatives of the members also contributed to the operation of the collective, creating another layer of non-recognized operational and even creative work, which historically can be interpreted within the underrated and invisible sphere of craftmanship.52 For instance, mothers of László Böszörményi and Éva Raffinger did needlework for many costumes and props, and the latter even filled in for a role at one performance when the actor was missing.53 Furthermore, as some members recalled, a number of established theatres in Budapest, including the Operetta Theatre, offered used items, such as costumes, props, reflectors, for the opening of the theatre.54 Last but not least, all members of the collective contributed through physical work to the building of Szkéné Theater, as they painted and hammered the walls, carried construction waste and pieces of the new set, which was captured by some photos. FIG. 7.

Collective work was thus an outcome of efforts and labour done by members of the collective, and also by civilians, including friends and relatives, as well as professionals, including colleagues working in theatres of the first public sphere. As Susan Bennett outlined almost twenty years ago, in order to acknowledge female contribution to theatre practices, it is not enough to supplement already existing histories, but a change of perspective and a different composition is needed.55 When writing the history of Hungarian amateur theatres, therefore, it is inevitable to (re)integrate female agents and give voice to their experiences. Besides exploring leading narratives of official reviews and cultural memory, other written documents, playbills, promptbooks, and photos in personal collections as well as oral histories and personal stories that have been explored by the current research can all help in writing the history of BME Literary Stage and the Szkéné Collective as a history of creative cooperation, allowing to highlight the labour of female participants as well as craftswomen, making their invisible work visible, recognized, and a vital part of (Hungarian) theatre history.

Bibliography

Bennett, Susan. „Decomposing History (Why Are There So Few Women in Theatre History?)”. In Theorizing Practice. Redefining Theatre History. Edited by W. B. Worthen, Peter Holland. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003, 71–87.

Bíró T., Csanády J. „Szkénések a Balaton partján”. A Jövő Mérnöke 16, No. 22. (1969): 7.

Bóta Gábor, ed. Arcok a Szkénéből. Budapest: OSZMI, 1998.

Cseh-Varga, Katalin. The Hungarian Avant-Garde and Socialism: The Art of the Second Public Sphere. London, New York, Oxford, New Delhi, Sydney: Bloomsbury, 2022.

Cseh-Varga, Katalin, Czirák, Ádám, eds. Performance Art in the Second Public Sphere. London and New York: Routledge, 2018. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315193106

Dévényi, Róbert, Keleti, István. A színjáték művészete II. Tankönyv a színjátszócsoportok és irodalmi színpadok szakmai vezetőinek oktatásához. Budapest: Népművelési Propaganda Iroda, n.d.

Dossier „Horgászok” ÁBTL-O-16268/2.

Dossier „Végső Géza” ÁBTL-M-27043.

Fahlenbrach, Kathrin, Sivertsen, Erling, Werenskjold, Rolf. eds. Media and Revolt: Strategies and Performances from the 1960s to the Present. New York and Oxford: Berghahn, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780857459992

Heltai Gyöngyi. „Színházművészeti Szövetség”, OSZMI Színháztörténeti Fórum, 2018, http://resolver.szinhaztortenet.hu/study/STD18381

Imre Zoltán, Kalmár Balázs. „Institute for People’s Cultural Education”. Hiányzó (színház)történetek, https://hiaszt.hu/institute-for-peoples-cultural-education/

Imre Zoltán, Ring Orsolya, eds. Szigorúan titkos: Dokumentumok a Kádár-kori színházirányítás történetéhez, 1972–1980. Budapest: PIM–OSZMI, 2018.

Interview with Éva Raffinger, 17 September 2022. Made by Kornélia Deres and Sára Ungvári.

Interview with Ilona Vercseg 30 July 2022. Made by Kornélia Deres and Sára Ungvári.

Interview with Katalin Andai, 30 June 2022. Made by Kornélia Deres and Sára Ungvári.

Interview with Katalin Takács, 10 September 2022. Made by Kornélia Deres and Sára Ungvári.

Interview with László Böszörményi, 1 September 2022. Made by Kornélia Deres and Sára Ungvári.

Jászay Tamás. „Egy színház átváltozásai: beszélgetés Nánay Istvánnal az ötvenéves Szkénéről”. Revizoronline, https://revizoronline.com/hu/cikk/8588/beszelgetes-nanay-istvannal-az-otveneves-szkenerol

Keleti István. A színjáték művészete I. Tankönyv a színjátszócsoportok és irodalmi színpadok szakmai vezetőinek oktatásához. Budapest: Népművelési Propaganda Iroda, 1966.

Kovács Zoltán, Tarnói Gizella, Váradi Zsuzsa, eds. A színház csak ürügy: Keleti István utolsó ajándéka. Budapest: Irodalom Kft. – Journal Art Alapítvány, 1996.

Lukanitschewa, Swetlana. „Against the Stream”. In Popular Music Theatre under Socialism. Edited by Wolfgang Jansen. Münster: Waxmann, 2020. 11–21.

Molnár Gál Péter. „Sebzett kiáltás”. Színház 3, No. 9. (1970): 28–31.

Monks, Aoife. „Costume At The National Theatre: A Curator’s Talk”, Studies in Costume and Performance 5, No. 1. (2020): 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1386/scp_00016_1

Monks, Aoife. „Curating Costume: Reflection”. In Performance Costume: New Perspectives and Methods. Edited by Sofia Pantouvaki, Peter McNeil, 63-66 (London: Bloomsbury, 2020). https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350098831.ch-006

Nánay István. „Amatőr színházak tündöklése és bukása”. Színháztudományi Szemle 19, No. 1. (1986): 179–251.

Nánay István. Profán szentély: színpad a kápolnában. Budapest: Alexandra Kiadó, 2007.

Records of University Stage 1965–1969, Hungarian National Theatre History and Museum, Manuscript Collection.

Regős Pál, Regős János, eds. Szkéné Színház 1968–2008: Színház ég és föld között. Budapest: Szkéné Színház, 2008.

Ring Orsolya. „A színházak pártirányítása a Kádár-korszakban: színházi témák az MSZMP KB Agitációs és Propaganda Bizottságának ülésein”, Levéltári Közlemények 79, Nos. 1–2. (2008): 197–214.

Roms, Heike. “Mind the Gaps: Evidencing Performance and Performing Evidence in Performance Art History”. In Theatre History and Historiography: Ethics, Evidence and Truth. Edited by Claire Cochrane, Joanna Robinson, 163–181. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137457288_9

Schuller Gabriella. “Kovács István Studio and Stances of Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde Theatre during the 1970s”. Institute of the Present, 2018, https://institutulprezentului.ro/en/2018/11/08/kovacs-istvan-studio/

- 1: My research is part of the project Missing (Theatre) Histories, supported by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office [Hiányzó (színház)történetek, NKFI 137873]. Besides members of the research group, I would especially like to thank Sára Ungvári, my student assistant, whose work contributed to the present essay. I am also grateful for the help of Gabriella Unger from the Historical Archives of the Hungarian State Security, and Beáta Huber, Tamás Halász and Mariann Sipőcz from the Hungarian Theatre Museum and Institute. Finally, I am more than grateful to Éva Raffinger and Péter Hidas, who generously allowed me to use their personal collections for the research, as well as to Ilona Vercseg, who provided great help in contacting many members of the theatre collective.

- 2: See, for instance: Rebecca Schneider, Performing Remains: Art and War in Times of Theatrical Reenactment (London: Routledge, 2011); Amelia Jones, Adrian Heathfield, eds., Perform, Repeat, Record: Live Art in History (Bristol and Chicago: Intellect, 2012); Heike Roms, “Archiving legacies: Who cares for performance remains?”, in Performing Archives / Archives of Performance, ed. by Gundhild Borggreen and Rune Gade, 35–52. (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press/University of Copenhagen, 2013); Heike Roms, “Mind the Gaps: Evidencing Performance and Performing Evidence in Performance Art History”, in Theatre History and Historiography: Ethics, Evidence and Truth, ed. by Claire Cochrane and Joanna Robinson, 163–181 (Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2016); Barbara Büscher, Franz Anton Cramer, eds., Fluid Access: Archiving Performance-Based Arts (Hildesheim: Olms Verlag, 2017); Paul Clarke, Simon Jones, Nick Kaye, Johanna Linsley, eds., Artists in the Archive (London: Routledge, 2018).

- 3: See, for instance: Katalin Cseh-Varga, Ádám Czirák, eds., Performance Art in the Second Public Sphere. Event-based Art in Late Socialist Europe (London and New York: Routledge, 2018); Tamás Scheibner, Kathleen Cioffi, „Archiving the Literature and Theatre of Dissent: Beyond the Canon”, in The Handbook of Courage: Cultural Opposition and its Heritage in Eastern Europe, ed. by Apor Balázs, Apor Péter and Horváth Sándor, 307–328 (Budapest: Institute of History, Research Centre for the Humanities, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 2018); Kürti Emese, Glissando és húrtépés: Kortárs zene és neoavantgárd művészet az underground magánterekben, 1958-1970 (Budapest: L’Harmattan, 2018); Juliana Fürst, Josie McLellan, eds., Dropping out of Socialism (New York: Lexington Books, 2017); Agata Jakubowska, Magdalena Radomska, eds., Horizontal Art History and Beyond: Revising Peripheral Critical Practices (New York: Routledge, 2022); Katalin Cseh-Varga, The Hungarian Avant-Garde and Socialism: The Art of the Second Public Sphere (London, New York, Oxford, New Delhi, Sydney: Bloomsbury, 2022).

- 4: Interview with Katalin Andai, 30 June 2022; Interview with Ilona Vercseg 30 July 2022; Interview with László Böszörményi, 1 September 2022; Interview with Katalin Takács, 10 September 2022; Interview with Éva Raffinger, 17 September 2022.

- 5: Kovács Zoltán, Tarnói Gizella, Váradi Zsuzsa, eds., A színház csak ürügy: Keleti István utolsó ajándéka (Budapest: Irodalom Kft. – Journal Art Alapítvány, 1996).

- 6: See in Kovács, Tarnói, Váradi, eds., A színház csak ürügy…

- 7: A very rich material on the BME Pantomime Theatre can be found at the Dance Archive of the Hungarian Theatre Museum and Institute as part of Pál Regős’ personal collection.

- 8: Regős Pál, Regős János, eds., Szkéné Színház 1968-2008: Színház ég és föld között (Budapest: Szkéné Színház, 2008), 23–62.

- 9: Website of Szkéné Theatre: https://www.szkene.hu/hu/szkene/tortenet.html

- 11: Nánay István, „Amatőr színházak tündöklése és bukása”, Színháztudományi Szemle 19, No. 1. (1986):179–251.

- 12: Kornélia Deres, Zoltán Imre, Veronika Darida, Gabriella Schuller, Missing [Theatre] Histories, project description, 2021.

- 13: A színház csak ürügy…; Gábor Bóta, ed., Arcok a Szkénéből (Budapest: OSZMI, 1998).

- 14: Regős, Regős, eds., Szkéné Színház 1968-2008…

- 15: Interview with Katalin Andai, 30 June 2022; Interview with Ilona Vercseg 30 July 2022.

- 16: The Kádár regime is referring to the era between 1956 and 1988, when Hungary’s leader was János Kádár, General Secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party. The start of the regime followed the suppression of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution (which was later officially referred to as counter-revolution), and therefore its first years were characterised by retributions, executions, and imprisonment. However, in 1963, under the slogan of “who is not against us, is with us”, Kádár pardoned many of those formerly imprisoned. The United Nations also ended its debate over the country, which was followed by a consolidation of the regime with increased trading and other collaborations with Western countries.

- 17: Imre Zoltán, Ring Orsolya, „A Kádár-kori színházirányítás a dokumentumok tükrében: 1970–1982”, in Szigorúan titkos: Dokumentumok a Kádár-kori színházirányítás történetéhez, 1972-1980, ed. by Z. Imre and O. Ring (Budapest: PIM–OSZMI, 2018), 11.

- 18: Swetlana Lukanitschewa, „Against the Stream”, in Popular Music Theatre under Socialism, ed. by Wolfgang Jansen (Münster: Waxmann, 2020), 18–19.

- 19: Ibid. 19.

- 20: Ring Orsolya, „A színházak pártirányítása a Kádár-korszakban: színházi témák az MSZMP KB Agitációs és Propaganda Bizottságának ülésein”, Levéltári Közlemények 79, Nos. 1–2 (2008): 197–214.

- 21: Imre, Ring, „A Kádár-kori színházirányítás…”, 12.

- 22: Ibid. 11-12; Lukanitschewa, „Against the Stream”, 19.

- 23: Heltai Gyöngyi, „Színházművészeti Szövetség”, OSZMI Színháztörténeti Fórum, 2018, last accessed 22.10.2022. http://resolver.szinhaztortenet.hu/study/STD18381

- 24: Zoltán Imre, Balázs Kalmár, „Institute for People’s Cultural Education”, Hiányzó (színház)történetek, last accessed 24.10.2022, https://hiaszt.hu/institute-for-peoples-cultural-education/

- 25: Imre, Kalmár, „Institute for…”

- 26: Keleti István, A színjáték művészete I. Tankönyv a színjátszócsoportok és irodalmi színpadok szakmai vezetőinek oktatásához (Budapest: Népművelési Propaganda Iroda, 1966); Dévényi Róbert, Keleti István, A színjáték művészete II. Tankönyv a színjátszócsoportok és irodalmi színpadok szakmai vezetőinek oktatásához (Budapest: Népművelési Propaganda Iroda, n.d.).

- 27: Imre, Ring, „A Kádár-kori színházirányítás…”, 12.

- 28: Katalin Cseh-Varga, Ádám Czirák, „Introduction”, in Performance Art in the Second Public Sphere, eds. K. Cseh-Varga, Á. Czirák (London and New York: Routledge, 2018), 2.

- 29: Cseh-Varga, The Hungarian Avant-Garde and Socialism…

- 30: Cseh-Varga, Czirák, „Introduction”, 7–8.

- 31: Kathrin Fahlenbrach, Erling Sivertsen and Rolf Werenskjold, eds., Media and Revolt: Strategies and Performances from the 1960s to the Present (New York and Oxford: Berghahn, 2014).

- 32: Gabriella Schuller, „Kovács István Studio and Stances of Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde Theatre during the 1970s”, Institute of the Present, 2018, last accessed 01.04.2022. https://institutulprezentului.ro/en/2018/11/08/kovacs-istvan-studio/

- 33: Nánay István, Profán szentély: színpad a kápolnában (Budapest: Alexandra Kiadó, 2007), 20–24.

- 34: Records of University Stage 1965–1969, Hungarian National Theatre History and Museum, Manuscript Collection

- 35: Heike Roms, “Mind the Gaps…”, 166.

- 36: Dossier „Végső Géza” M-27043. Furthermore, Tamás Varga’s name was mentioned in the renowned state security dossier entitled „Horgászok”, which gathered reports against the team of Apartment Theatre at Dohány Street, who eventually emigrated in 1976. In one of the reports, Varga spoke about his negative opinion on the group’s work, as well as their 1973 premiere in Wroclaw. ÁBTL-O-16268/2, 92-94.

- 37: In November and December 2022 further interviews are to be conducted with Péter Hidas, Ilona Harsay, Alfréd Wiegmann, and László Pap.

- 38: Roms, “Mind the Gaps…”, 166.

- 39: The video interviews will be published on the project website of Missing (Theatre) Histories. URL: https://hiaszt.hu/szkene-szinhaz/

- 40: Nánay, „Amatőr színházak tündöklése…” [English translation by me – K.D.]

- 41: Interview with Katalin Andai, 30 June 2022; Interview with Ilona Vercseg, 30 July 2022; Interview with Katalin Takács, 10 September 2022.

- 42: Interview with Katalin Andai, 30 June 2022; Interview with Ilona Vercseg 30 July 2022; Interview with László Böszörményi, 1 September 2022; Interview with Katalin Takács, 10 September 2022; Interview with Éva Raffinger, 17 September 2022.

- 43: Interview with Katalin Takács, 10 September 2022.

- 44: Ibid.

- 45: Molnár Gál Péter, „Sebzett kiáltás”, Színház 3, No. 9. (1970): 28–31, 29.

- 46: Jászay Tamás, „Egy színház átváltozásai: beszélgetés Nánay Istvánnal az ötvenéves Szkénéről”, Revizoronline, last accessed 18.10.2022 https://revizoronline.com/hu/cikk/8588/beszelgetes-nanay-istvannal-az-otveneves-szkenerol

- 47: Bíró T., Csanády J., „Szkénések a Balaton partján”, A Jövő Mérnöke 16, No. 22. (1969): 7.

- 48: Interview with Katalin Andai, 30 June 2022.

- 49: Ibid.

- 50: Interview with Katalin Andai, 30 June 2022; Interview with Ilona Vercseg 30 July 2022; Interview with László Böszörményi, 1 September 2022.

- 51: Interview with Katalin Andai, 30 June 2022; Interview with Ilona Vercseg 30 July 2022; Interview with Katalin Takács, 10 September 2022; Interview with Éva Raffinger, 17 September 2022.

- 52: See the critical work by Aoife Monks on theatre costumes and virtuosity. Aoife Monks, „Costume At The National Theatre: A Curator’s Talk”, Studies in Costume and Performance 5, No. 1. (2020): 101–111; Aoife Monks, „Curating Costume: Reflection”, in Performance Costume: New Perspectives and Methods, ed. by Sofia Pantouvaki and Peter McNeil (London: Bloomsbury, 2020), 63–66.

- 53: Interview with László Böszörményi, 1 September 2022; Interview with Éva Raffinger, 17 September 2022.

- 54: Interview with László Böszörményi, 1 September 2022; Interview with Éva Raffinger, 17 September 2022.

- 55: Susan Bennett, „Decomposing History (Why Are There So Few Women in Theatre History?)”, In Theorizing Practice. Redefining Theatre History, ed. by W. B. Worthen, Peter Holland (London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), 71–87.